'There's Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension' by Hanif Abdurraqib

'I never wanted to be anywhere other than where I was, my two feet planted on concrete that was breaking, but satisfied to still be of use.'—Review #237

I had my fingers crossed that you would vote in our recent poll for me to review Hanif Abdurraqib’s new book, ‘There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension.’ I have long admired Abdurraqib’s work, as I’ve mentioned repeatedly, and have featured it several times, including ‘They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us,’ 'Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest' and 'A Little Devil in America: In Praise of Black Performance.' I was especially excited to read ‘There’s Always This Year’ because basketball is my favorite sport, which I’ve also mentioned repeatedly, and I was eager to see what Abdurraqib—a National Book Award finalist and MacArthur Foundation ‘genius’ grant recipient—would write about it. So when the final tally broke this way, I was like:

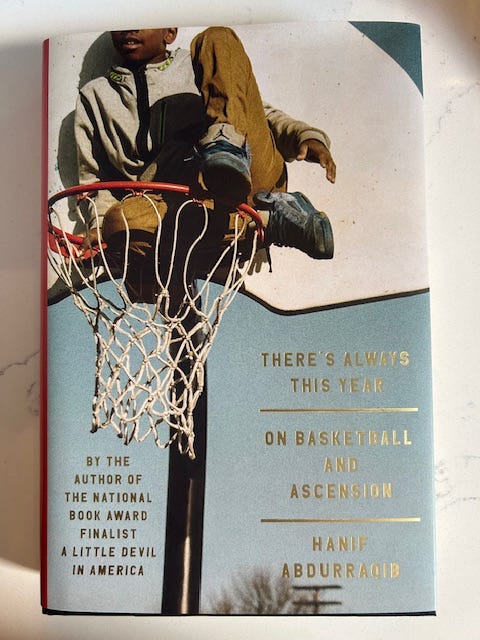

Here’s the book’s cover:

‘There’s Always This Year’ is part philosophical meditation, part memoir, part love letter to a place and part sports-fan chronicle that’s structured like a basketball game, literally. There’s a pregame opening section and four quarters where paragraphs are broken up by a countdown clock (you’ll see how that works below). There are timeouts and intermissions that include poems and short stories. There are players—people in Abdurraqib’s life from his hometown of Columbus, Ohio, and elsewhere, characters from movies, notable basketball players and others who sub into and out of the narrative—with the most minutes going to Abdurraqib himself and to:

While the book touches on many themes, including love, loss, community, music, art and anger, among others, it primarily is about coming home. How we can be compelled to leave home—willingly or otherwise—how we can get lost while we’re away, and how we can be renewed when we return. We see moments in Abdurraqib’s life where he loses a job, falls behind on the rent, gets evicted and is briefly unhoused, forced to sleep in a storage unit. We see him in trouble with the law and briefly incarcerated. We see him living in another city, hoping a new location can help turn his life around. And we see him return to Columbus, and get his feet under him as a writer in a place he has loved and that has loved him. He reconnected with this love not only among family and friends, but also through neighborhood basketball courts where people come together to hang out, play ball or to watch others become legends. We also see LeBron James, the basketball prodigy from Akron who was destined to lift Ohio to glory, and his parallel story of leaving and returning. Abdurraqib recounts seeing the much-hyped James in high school before he made the jump directly into the NBA. He reminds us of the fans’ faith that James would lead the Cleveland Cavaliers to championships, and how some of them felt betrayed when he made his ‘Decision’ to take his talents to South Beach. But he also relates how the fans’ love was restored and strengthened when James returned to Cleveland and delivered a championship in 2016:

There are beautiful moments throughout this book, like Abdurraqib’s ‘timeout’ vignette about meeting John Glenn when he was in middle school. He asked the former astronaut and senator whether he was ever afraid, and Glenn replied that he had never been more afraid than he had been curious. I also like the ‘intermission’ story about the scene in Spike Lee’s movie ‘He Got Game’ where Denzel Washington and Ray Allen square off in a father-son basketball battle. Abdurraqib uses this to explore his relationship with his father. And I like how he captures the way winning basketball can unite people; I was pleasantly reminded of how New York seems way more upbeat when the Knicks are good (I can’t wait for next season!). But I’m sad to admit that I didn’t love ‘There’s Always This Year’ as much as I wanted to. Despite its moments of brilliance, I thought it dragged at times and felt overlong. I kept thinking about a basketball player dribbling too much, you want them to pass the ball or take a shot and keep things moving. At those times I struggled to connect. My mind was like:

Abdurraqib has written a deeply personal book, and I’m glad that he shared his vulnerable moments as well as his fascinating insights with us. Although it didn’t always work for me, I’m glad I read it and am still a huge fan of his work. I look forward to what he writes next.

An opening excerpt:

5:00

You will surely forgive me if I begin this brief time we have together by talking about our enemies. I say our enemies and know that in the many worlds beyond these pages, we are not beholden to each other in whatever rage we do or do not share, but if you will, please, imagine with me. You are putting your hand into my open palm, and I am resting one free hand atop yours, and I am saying to you that I would like to commiserate, here and now, about our enemies. And you will know, then, that at least for the next few pages, my enemies are your enemies.

But there’s another reality: to talk about our enemies is also to talk about our beloveds. To take a windowless room and paint a single window, through which the width and breadth of affection can be observed. To walk to that window, together, if you will allow it, and say to each other How could anyone cast any ill on this. And we will know then, collectively, that anyone who does is one of our enemies. And so I’ve already led us astray. You will surely forgive me if I promised we would talk about our enemies when what I meant was that I want to begin this brief time we have together by talking about love, and you will surely forgive me if an enemy stumbles their way into the architecture of affection from time to time. It is inevitable, after all. But we know our enemies by how foolishly they trample upon what we know as affection. How quickly they find another language for what they cannot translate as love.

4:25

Our enemies believe the twisting of fingers to be a nefarious act, depending on what hands are doing the twisting and what music is echoing in the background and upon which street the music rattles windows. Yet there is a lexicon that exists within the hands I knew, and still know. One that does not translate to our enemies, and probably for the better. Some by strict code, some by sheer invention, but I know enough to know that the right hand fashioned in the right way is a signifier—an unspoken vocabulary. Let us, together, consider any neighborhood or any collective or any group of people who might otherwise be neglected in the elsewheres they must traverse for survival, be it school or work or the inside of a cage. Let us consider, again, what it means to have a place as a reprieve, a people as reprieve, somewhere the survival comes easy. Should there not be a language for that? A signifier not only for who is to be let in but also who absolutely gotta stay the fuck out?

Who Hanif Abdurraqib thanked:

Hanif Abdurraqib dedicated toe book to several people who had died, including Ohio-based activists. I looked several of them up, and a few had died by suicide. He thanked various people who helped him with the book, from friends to editors to designers. (The list includes a former coworker of mine. Small world.) He also thanked his community of peers, especially a writers’ group chat. And he offered gratitude to the people who ‘put the nets up,’ ‘painted the lines’ and ‘swept the glass off the courts.’

My rating:

‘There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension’ by Hanif Abdurraqib was published by Random House in 2024. 334 pages, including index. $29.76 at Bookshop.org.

What’s next:

Next week, I’ll share the first installment of the books I bought while traveling this summer. The following week’s newsletter will return to short-book summer with:

Before you go:

ICYMI: Review #236

Read this: The Booker Prize 2024 longlist is out! I haven’t ready any of them, have you? The one I am most interested in is ‘James’ by Percival Everett, but are there others you’d recommend as well?

Read this, too: August is Women in Translation month. If you’re looking for recommendations for translated literature by women, Books on GIF has you covered. Here’s a list!

If you enjoyed this review:

Thanks for reading, and thanks especially to Donna for editing this newsletter!

Until next time,

MPV

I wanted to read this anyway but now I want to read it EVEN more! Thanks for a great review Mike!

Well, well, well. I think you've convinced me to read a basketball book. I love that there's more meat to it than I thought there'd be.