'Middlemarch' by George Eliot

'The business was felt to be so public and important that it required dinners to feed it, and many invitations were just then issued and accepted on the strength of this scandal...'—Review #216

I got a good feeling about George Eliot’s masterpiece ‘Middlemarch’ when I pulled it off the shelf at a used bookstore. You could say the copy of this 800-plus-page novel was damaged by previous owners: the spine is cracked, the cover is frayed at the edges, and the pages are yellowed and worn (some even have stains where food had dripped). To me, though, these felt like physical markings of love and enjoyment left from many readings and re-readings. Although I never, ever, crack the spine of a paperback, I imagined a previous owner doing it to get this classic to stay open while they commuted on the subway or waited for a plane to take them on a vacation. Perhaps the pages were faded and softened by the sun as the reader relaxed on the beach. The cover probably got roughed up in luggage, totes or other bags from being taken everywhere in anticipation of a stolen moment to sneak in a chapter or two. And the stains were likely due to the reader being so engrossed they didn’t see the dollop of grease or sauce at the edge of their fork ready to fall.

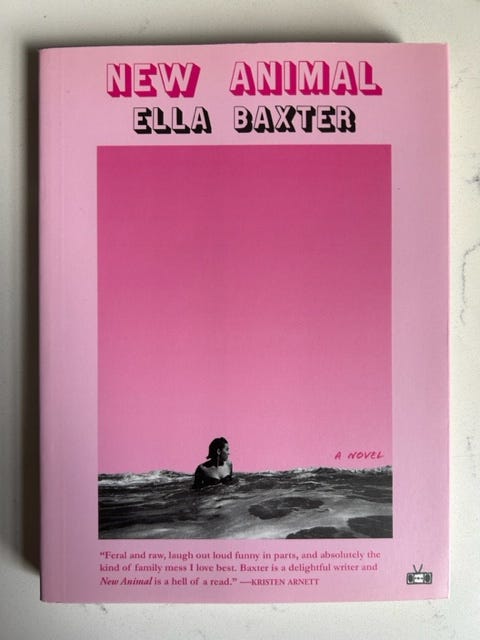

Here’s the cover:

‘Middlemarch’ opens in an English countryside town of the same name in 1829, when England appears on the cusp of change. A Reform Bill to expand voting rights (slightly) beyond wealthy landowners is being considered by Parliament, as is the abolition of slavery (the real versions of these measures passed in 1832 and 1833, respectively). Residents hear about a great metal thing called the railroad that is approaching their area. Medical practitioners debate whether new scientific methods of healing should replace traditional elixirs and techniques of bleeding and applying leaches to patients. We meet many inhabitants of Middlemarch, including young people hoping to marry well and leave their mark on the world, various wealthy gentlemen (respectable and otherwise), clergymen and, most enjoyably, gossips. Chief among this milieu is Dorothea Brooke, a young woman from a wealthy family who’s determined to expand her intellectual horizons and use her privileged status to help people. Dorothea and her sister, Celia, live with their uncle (I forget what happened to their parents) who invites guests to dinner. One of them is Edward Casaubon, a middle-aged and rough-looking local religious figure and scholar who’s said to be doing important work on mythologies, or something. Dorothea figures that Casaubon is her best shot at a husband who will feed her hunger for knowledge, and Casaubon figures Dorothea will be a helpful assistant, so they plan to get married. This unleashes a wave of gossip in town, and everyone, including Dorothea’s sister, is like:

After a disastrous honeymoon in Rome, where Casaubon reveals himself to be a controlling husband and a mediocre intellectual whose big project is going nowhere, Dorothea is like:

Luckily, Casaubon dies. But before he does, he makes a final attempt to control Dorothea from beyond the grave by including in his will a stipulation that his wealth and property should be revoked from her if she marries Casaubon’s age-appropriate and handsome cousin, Will Ladislaw. Dorothea got to know Ladislaw on her doomed trip to Rome, and the pair formed an instant connection that stoked Casaubon’s jealousy and deeply felt disdain for the younger man. After learning about the updated will, Dorothea vows never to marry again. She settles for a life of widowhood and pet projects, like donating to the town’s new hospital. Then we start to hear the distant rumblings of a major scandal. Once it started to take shape, I sat up straight like:

I love gossip, as you all know. And while I can’t give too much away, the final section of the book includes a dream scenario for someone like me, with murder, slander, blackmail and romantic misunderstandings. Tea is served in huge quantities, and I was like Kermit the Frog drinking it up:

Gossip is such a powerful force in ‘Middlemarch’ that it practically takes on human form through the novel’s unnamed narrator. A spectral presence who can be funny, sarcastic and deadly serious, the narrator reminds me of the Ghost of Christmas Past, helping us to hover over and spy on characters’ lives to see their inner thoughts, fears and motivations, but not in a creepy way like Spider-Man here:

Virginia Woolf reportedly said ‘Middlemarch’ is a novel ‘written for grownup people.’ I completely agree. Not only do we see characters wrestle with adult problems like financial mismanagement, public shaming and grief over a miscarriage, but also the book highlights gender and class issues. We see the constraints marriage and society place on women, including not being allowed to use their own money or to fully express their emotions (crying is often a stand-in for rage). It also acknowledges how the privileges and wealth enjoyed by the featured characters have come at the expense of enslaved and working people. In one memorable scene, Dorothea’s uncle is confronted by one of his tenant farmers who seethes with resentment and anger. In another, a rich guy named Fred tries to get a job to impress the hard-working Mary, but when he’s asked to copy a list of figures, his boss (Mary’s dad) discovers Fred’s handwriting is illegible. The narrator tells us many gentlemen had terrible handwriting because penmanship was a sign of lower rank. (Fun fact: If bad handwriting were a sign of nobility, I’d be the King of England!) I really liked how the book has a strong sense of justice (many of the characters who exploit or malign women come to a bad end) and how it feels in sync with many of our era’s sensibilities and concerns. Even though the book was written nearly 150 years ago, I kept thinking:

Another grownup aspect to ‘Middlemarch’ is its clear-eyed understanding about how much of adult life is shaped by failure and crushed dreams. As you’ll see in the excerpt below, this depressing reality is conveyed through Eliot’s beautiful and often humorous writing. At times, a brutal truth is so elegantly and lightheartedly delivered, you won’t know whether to cry or laugh, like:

‘Middlemarch’ is a tremendous book, and I could go on and on about it. There is so much that time and space won’t allow me to fit in here, so I’d love it if we could keep talking about it in the comments. Even though it took me a full month to get through it, ‘Middlemarch’ is one of the best books I’ve read this year and I can’t recommend it enough. I’m excited to be yet another reader who has enjoyed this well-worn copy. (I got so involved in the narrative, that I, too, dribbled something onto the pages—water, in my case.) If you’re looking for a book that’s excellently written and as smart as it is sharp, or if you want to immerse yourself in a fleshed-out world with fascinating characters, I strongly encourage you to read this classic.

How it begins:

Who that cares much to know the history of man, and how the mysterious mixture behaves under the varying experiments of Time, has not dwelt, at least briefly, on the life of Saint Theresa, has not smiled with some gentleness at the thought of the little girl walking forth one morning hand-in-hand with her still smaller brother, to go and seek martyrdom in the country of the Moors? Out they toddled from rugged Avila, wide-eyed and helpless-looking as two fawns, but with human hearts, already beating to a national idea; until domestic reality met them in the shape of uncles, and turned them back from their great resolve. That child-pilgrimage was a fit beginning. Theresa’s passionate, ideal nature demanded an epic life: what were many-volumed romances of chivalry and the social conquests of a brilliant girl to her? Her flame quickly burned up that light fuel; and, fed from within, soared after some illimitable satisfaction, some object which would never justify weariness, which would reconcile self-despair with the rapturous consciousness of life beyond self. She found her epos in the reform of a religious order.

That Spanish woman who lived three hundred years ago was certainly not the last of her kind. Many Theresas have been born who found for themselves no epic life wherein there was a constant unfolding of far-resonant action; perhaps only a life of mistakes, the offspring of a certain spiritual grandeur ill-matched with the meanness of opportunity; perhaps a tragic failure which found no sacred poet and sank unwept into oblivion. With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardour alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse.

Some have felt that these blundering lives are due to the inconvenient indefiniteness with which the Supreme Power has fashioned the natures of women: if there were one level of feminine incompetence as strict as the ability to count three and no more, the social lot of women might be treated with scientific certitude. Meanwhile the indefiniteness remains, and the limits of variation are really much wider than any one would imagine from the sameness of women’s coiffure and the favourite love-stories in prose and verse. Here and there a cygnet is reared uneasily among the ducklings in the brown pond, and never finds the living stream in fellowship with its own oary-footed kind. Here and there is born a Saint Theresa, foundress of nothing, whose living heart-beats and sobs after an unattained goodness tremble off and are dispersed among hindrances, instead of centering in some long-recognizable deed.

My rating:

‘Middlemarch’ by George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) was originally published in 1871-72, and a second edition was published in 1874. It was published by Penguin Classics in 1994 and 2003. 853 pages, including notes. $16.74 at Bookshop.org.

What’s next:

Before you go:

ICYMI: Review #215

Read this: I’m looking forward to reading all 16 installments (free subscription required) of Book Post’s ‘Summer Reading of Middlemarch’ read-along with Mona Simpson now that I’ve finished the book. You should check out the series, too.

Read this, too: ‘From Friends to Lovers: The Fanfic-to-Romance Pipeline Goes Mainstream’ (subscription required) by Elizabeth Held, our friend and preeminent newsletter writer, in Vulture is a great piece. It shows how book publishers are turning to writers of fan fiction around properties like ‘Star Wars’ (remember the ‘Reylos’?) and Harry Potter to write best-selling romance novels. (I totally forgot that ‘Fifty Shades of Grey’ started out as ‘Twilight’ fan fiction.) I’m terrified of, and have been carefully avoiding, wading into the intense world of romance novels, but I will have to do it soon because…

Poll results: Thanks to all of you who voted in our poll! ‘Sci-fi, fantasy, romance series’ edged out ‘Zora Neale Hurston nonfiction,’ as you can see in the final results:

Also, read this: Donna flagged another Vulture piece (subscription required) to me recently about the team behind the new movie ‘Bottoms.’ In it, actor Ayo Edebiri reveals that her go-to karaoke song is ‘Wuthering Heights’ by Kate Bush, which is also MY go-to karaoke song. ‘It’s pure terrorism to do this song,’ she says. Donna and my besties Marta and Nicole, who were present the last time I sang it, would certainly agree.

If you enjoyed this review:

Thanks for reading, and thanks especially to Donna for editing this newsletter!

Until next time,

MPV

Newsletters you ♥️ the most

‘The Secret History’ by Donna Tartt | ‘Possession: A Romance’ by A.S. Byatt

'Trust' by Hernan Diaz | ‘Near to the Wild Heart’ by Clarice Lispector

‘The Bell’ by Iris Murdoch | ‘Dune’ by Frank Herbert | ‘Boulder’ by Eva Baltasar

‘We Were Once a Family’ by Roxanna Asgarian | ‘The Nineties’ by Chuck Klosterman | ‘Madame Bovary’ by Gustave Flaubert | ‘Sweet Days of Discipline’ by Fleur Jaeggy

The final lines of Middlemarch have glued themselves to my brain. Such a fantastic tome!

This is in my humble opinion the best novel of all time! I probably read it every ten years and get something different every time and its concluding paragraph gave me the subtitle for my first book. Do read @monasimpson @Bookpost as I found the discussion fascinating. But this is a lovely summary, I'm so glad you enjoyed it!