Three Books You Can Finish in a Day or Two

'Pedro Páramo' by Juan Rulfo, 'Pisti, 80 Rue de Belleville' by Estelle Hoy and 'The Employees' by Olga Ravn—Review #233

I don’t feel like reading long books this summer. Those tomes are for winter, when it’s cold, dark and dreary, and you can curl up under a blanket with a cup of tea while you read. Summer is a time to be outside—at the beach, on a hike or hanging out with friends—so I’m adjusting my reading accordingly. (I’m also making other changes to this newsletter, noted below.) I’m selecting from my ever-growing TBR pile only those books that can fit in my back pocket, slide easily into luggage and that I can breeze through. I figured many of you might be looking to have a short-book summer, too, so here are three to consider. One is an absolute must, if you can find it.

‘Pedro Páramo’ by Juan Rulfo

A man fulfills his dying mother’s wish and sets out to find his estranged father, Pedro Páramo. When he arrives at his father’s last-known location in rural Mexico, he learns that Páramo is already dead. And maybe everyone else in the town is dead, too, like the old woman who takes him in for the night. If she isn’t a ghost exactly, perhaps she is a hallucination, like the sounds the man hears—screaming and other voices. The area where he’s ventured was once dominated by his father and is haunted by painful memories. We learn why as Rulfo’s surreal novel jumps around in time, like a Tarantino movie or an old person rambling. The man discovers that his father was a businessman, a landowner and a womanizer who bribes or strong-arms judges, clergymen and others for power. He uses courts to steal people’s land, he makes a marriage of convenience to acquire more, and he uses henchmen to exert influence, political or otherwise. He also lets another gun-toting son run wild and cause havoc. But Pedro Páramo also has a thoughtful side. He’s a complicated fellow, one who is initially underestimated but then prevails. He reminded me a bit of:

‘Pedro Páramo’ has been an influential book for many authors, particularly Gabriel García Márquez, who wrote the foreword. García Márquez describes how the nonlinear structure of the book—which he finished in one evening and often reread—changed his writing. While I did not have the same awe-inspired reaction, I agree that the book is best consumed in one go, or as close as possible. Because of its structure and its creative use of quotation marks, it’s easy to get lost. I initially had tried reading the book during a recent work trip to London in fits and starts at the airport, on the plane and after work. No good. I was constantly like:

So I started all over once I returned to Brooklyn, and I read it straight through in roughly an afternoon. Much better. It’s still a challenging read, and I’m not sure what the book is ultimately about. Maybe it’s about how shared trauma and collective memory can ripple through generations, and have a physical affect on people and the landscape. I’ll have to read other reviews. Donna, who also read it and had encouraged me to do the same for months, also got lost at times. But she, like García Márquez, looks forward to reading it again. While this book won’t work for every reader, those of you who are into magical realism, or surreal books or intricately crafted nonlinear narratives should definitely check it out.

An opening excerpt:

I came to Comala because I was told my father lived here, a man named Pedro Páramo. That’s what my mother told me. And I promised her I’d come see him as soon as she died. I squeezed her hands as a sign I would. After all, she was near death, and I was of a mind to promise her anything. “Don’t fail to visit him—she urged—. Some call him one thing, some another. I’m sure he’d love to meet you.” That’s why I couldn’t refuse her, and after agreeing so many times I just kept at it until I had to struggle to free my hands from hers, which were now without life.

Before this she had told me:

—Don’t ask him for anything. Just insist on what’s ours. What he was obligated to give me but never did…Make him pay dearly, my son, for the indifference he showed toward us.

—I will, Mother.

I never thought I’d keep my promise. Until recently when I began to imagine all kinds of possibilities and allowed my fantasies to run free. And that’s how a whole new world started swirling around in my head, a world built on expectations I had for that man named Pedro Páramo, my mother’s husband. That’s why I came to Comala.

My rating:

‘Pedro Páramo’ by Juan Rulfo was originally published by Fondo de Cultura Económica. It was translated from the Spanish by Douglas J. Weatherford and published by Grove Press in 2023. The foreword by Gabriel García Márquez was originally published in 1980, and translated from the Spanish by N.J. Sheerin in 2014. 129 pages, including foreword and translator’s note. $15.81 at Bookshop.org.

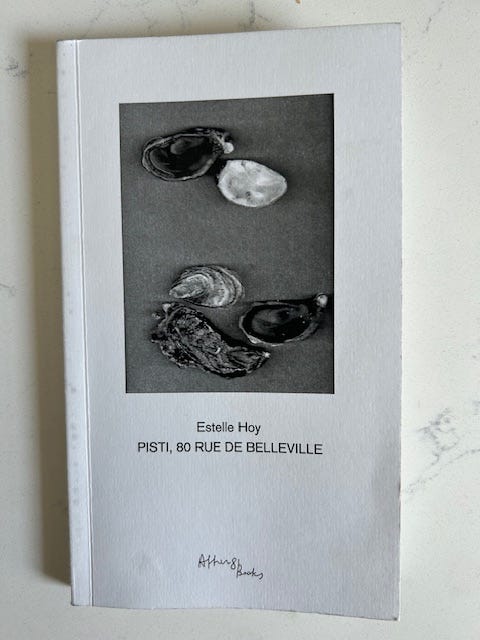

‘Pisti, 80 Rue de Belleville’ by Estelle Hoy

Elke is en route to an artist’s retreat in rural France, but first finds herself in a Paris apartment for a gathering that’s part house party, part political salon and part orgy. She meets an intense, younger woman named Pisti, a Hungarian who’s a militant leftist with strong opinions about Brexit and who has a liberal view about being fully clothed. Elke and Pisti spar (Pisti sharply earnest, Elke world-weary) over the usual intellectual things—who’s read the right underground literature, who’s formed the purest political critique, who’s lived the truly authentic life—and as they do, and as the Muscadet flows, their sexual tension rises. (So much so, it reminded me that all political discussion at bars or parties is just a form of foreplay.) We learn that Elke is roughly in her late thirties and, after years of living a political activist’s and artist’s life in Manhattan’s East Village, is now in Europe teaching posh university students about social-justice issues. She’s into polyamory (her partners are elsewhere babysitting her daughter), but her ulterior mission at the party is seducing Jean, the hot, chunky-sweater-wearing son of a poet and a Quebecois separatist. I was riveted to Elke’s story. You all know I love gossip and drama, and Elke is so messy. Would she make it to the retreat? Would she run off with Pisti? Would Jean be another conquest? I was like:

I love so many things about this book. It’s a brisk and engaging read. There’s plenty to chew on intellectually and politically, but it doesn’t get bogged down. Some of the chapters include script-like dialogue that keeps things moving. There are also track listings (one is ‘Running Up That Hill,’ and you know me when it comes to Kate Bush: ♥️♥️♥️). I love how it tackles heavy Gen X themes like selling out and how to remain true to one’s self and one’s art when there are bills to pay. I love how weary Elke sounded while discussing politics, art, throuples—basically every clever thought has been thought before, and pretentiousness is exhausting. And I love how it reminded me of younger days, when you would meet someone at a party and have an intense conversation for a few hours, and how those hours felt like the most important of your life. But most of all, I love that this book came to me through pure serendipity. You never know where or when you’re going to find your next favorite book, and for me it was at an airport bookstore in Tampa. I still can’t get my mind around it:

‘Pisti, 80 Rue de Belleville’ was published by a small, independent press in Paris, yet, somehow, several copies made their way to the BookLink in Terminal E. Who is ordering books for Tampa International Airport?! I must know! That person needs a medal and a raise! Even the cashier was like, ‘Oh, what’s this?’ I’ll tell you what it is: a tremendous book and the best I’ve read all year. I’m so happy the universe put Estelle Hoy’s gem in my path. If you can find this novel, get it. (The only copy in New York might be at McNally Jackson’s SoHo location, in the Art Instructional section. 🤷♂️) I highly recommend it.

An opening excerpt:

I met a woman, covertly anti-intellectual. We had a meager breakfast of stale bread and pickles dipped in black coffee. She served the coffee in second-hand saucers covered in yellow and blue roses. She’d been having occasional sex with a conservative who recently liberated herself from her Catholic school upbringing. Neither of them could agree on anything political, but enjoyed their burgeoning sexuality nonetheless. They would lie on a mattress on the floor in floral nighties and book nights away at sleazy hotels to keep things interesting. The year before, she’d lived abroad in an anarchist community in the outskirts of Berlin that put hairs on her chest in all the right ways. She asked me if I was familiar with Dada. I told her I was fond of Hannah Höch and that I’d written her one time. She seemed to like me more after that.

She tells me it’s her third attempt in overcoming depression in that overtly effete way people do when talking about depression. She burned the toast but scraped it forcefully and threw it underneath me. She was disillusioned with the intellectual left, and I similarly weary, listened to her bemoan England’s betrayal of representative democracy. She was from Budapest but antsy to reinforce, '“From Pest, not Buda. Always Pest, flat like a prairie.” She called herself Pisti and planned to take a course in pre-revolutionary Russian literature at Berkeley the following year, intending not to pay. I nodded. I was too busy dipping burnt toast into burnt coffee.

Who Estelle Hoy thanked:

Author Chris Kraus, who wrote an introduction to the novel, ‘for both her character of Pisti and her character of person.’

My rating:

‘Pisti, 80 Rue de Belleville’ by Estelle Hoy was published by After 8 Books in 2019 and 2022. 114 pages. $14.88 at Bookshop.org.

‘The Employees’ by Olga Ravn

‘The Employees’ by Olga Ravn is a ‘workplace novel of the 22nd century’ that follows the fate of human and android crew members on a spaceship that’s orbiting a distant planet. The crew of the Six Thousand Ship has retrieved several objects from the alien world, called New Discovery, and is having increasingly odd and troublesome interactions with them. Nothing as bad as the xenomorphs from the ‘Alien’ movies, but something always seems to go wrong for people in space, right? Turns out, working on a spaceship circling a strange new world is just as soul-killing and depressing as working an office job here on Earth, and the objects have exacerbated this. Apparently, in space, no one can hear you screaming at your desk.

As you’ll see below, the novel is composed of statements from workers, human and humanoid (as the book calls artificial people). Some statements are as long as a page or two, some are only a sentence or a paragraph. They recreate, piece by piece, life and work on Six Thousand Ship, the crisis that befalls the crew and the unsettling response by their corporate employers. To explain more would give too much away, but this novel offers fascinating commentary on contemporary workplace issues such as layoffs and the coming of AI. Those of us who have been working for a long time have near-constant anxiety about being replaced by a younger person who can be paid less, or by a machine. Same goes for space workers. But Ravn demonstrates that while the next generation always believes they’re immortal and indestructible, they’re on borrowed time, too. And she shows how technology lauded one day can be obsolete the next. Productivity is all that matters. Even though it’s science fiction, this novel is fascinating and of the moment. Many times it had me thinking:

‘The Employees’ is a chilling and vital book. You should read it. (For a more in-depth look, please check out this review from my awesome colleague Book Notes.)

An opening excerpt:

The following statements were collected over a period of 18 months, during which time the committee interviewed the employees with a view to gaining insight into how they related to the objects and the rooms in which they were placed. It was our wish by means of these unprejudiced recordings to gain knowledge of local workflows and to investigate possible impacts of the objects, as well as the ways those impacts, or perhaps relationships, might give rise to permanent deviations in the individual employee, and moreover to assess to what degree they might be said to precipitate reduction or enhancement of performance, task-related understanding, and the acquisition of new knowledge and skills, thereby illuminating their specific consequences for production.

Who Olga Ravn thanked:

Danish artist Lea Guldditte Hestelund ‘for her installations and sculptures, without which this book would not exist.’ You can see some of her work here.

My rating:

‘The Employees’ (De ansatte) by Olga Ravn was published by Gyldendal Group Agency in 2020. It was translated from the Danish by Martin Aitken and published in the U.K. by Lolli Editions in 2020. It was published by New Directions in 2022 and 2023. 125 pages. $13.90 at Bookshop.org.

What’s next:

Books on GIF does not solicit review copies. We feature books we purchase at independent bookstores around New York City and on our travels, or were borrowed electronically from the Brooklyn Public Library.

Before you go:

ICYMI: Review #232

Some news: Books on GIF is going weekly this summer, starting July 7. You’ll still get book reviews every other Sunday, and in between we’ll rotate a question thread and a roundup of articles I’m reading and books I’ve added to the TBR. Our aim is to try this for July and August, but if you guys enjoy the extra content, we’ll keep it going after Labor Day. We look forward to having more opportunities to engage with you!

If you enjoyed this review:

Thanks for reading, and thanks especially to Donna for editing this newsletter!

Until next time,

MPV

Short book summer had me chuckling. Lots of good reads to consider – thank you!

I fell hard for Pedro Paramo. Definitely not traditional easy-to-follow narrative, very trippy, so you just go with it. It’s like Roberto Bolano on a micro dose of acid. The Pisti novel sounds great—very cool how you find these gems. Thank you for livening up Sunday morning.