'The Little Friend' by Donna Tartt

'At one time, she was very sure; the idea had felt right, and that was the important thing.'—Review #224

My favorite thing about buying used books is finding little clues left by previous owners. This copy of Donna Tartt’s second novel, ‘The Little Friend,’ has many. The price sticker on the back indicates it was originally purchased at Dubray Books in Ireland for €12.99. A prior reader appears to have gotten a paper cut reading page 36, which has tiny smears that look like blood. The book was kept in a damp place, maybe on Long Island where I found it, because some of the pages have mold stains. There could be a dried drip or two of orange juice, too (or maybe that’s just more mold). It also appears to have been kept someplace warm and packed tightly on a shelf or under a book pile because the glue has softened and reset in a slanty shape. The book also seems to have been read several times because the spine has multiple cracks, and the cover is creased and beat up. What do all these clues add up to? A definitive narrative about the trans-Atlantic journey of my copy? Certainly not. It’s all merely fun conjecture in my head. But guesses have a way of congealing into something that feels like facts, as the precocious protagonist of this dark and unsettling novel discovers.

Here’s the cover:

Harriet is a 12-year-old girl living in a small Mississippi town in the late 1970s. When she was an infant, her older brother, Robin, was murdered in broad daylight outside her family’s home as they were preparing to celebrate Mother’s Day. He was 9 years old. The crime was never solved, but its shadow has long haunted Harriet’s family. Her mother, Charlotte, has become a hoarder who spends her days sleeping or drifting through the house in a drug-induced stupor. Her father got a job in another city and rarely comes around. Her grandmother and three great aunts never talk about Robin’s death, even though they reminisce about other family tragedies all the time. Harriet is headstrong, stubborn, bratty and smart beyond her years. As her summer break from school starts, she connives a way to duck going to a hated religious camp. Instead, she forges her father’s signature on a check to pay for membership at a country club where she can go swimming and practice holding her breath like Harry Houdini, one of her heroes. She also gives herself summertime projects. One is to place first in the library summer reading contest. The other is solving her brother’s murder.

She enlists her pal Hely—he’s a goofy and garrulous Watson to her Holmes—and they begin their quest. Harriet eventually reckons that Danny Ratliff, a member of a ne’er-do-well local family involved in drugs and crime, who’s roughly the same age Robin would be, must be the culprit. She changes her mission from crime solving to getting revenge like:

Her plan is to catch a venomous snake—like one of the local cottonmouths or copperheads—and get it to bite Danny. Meanwhile, a pastor of a church where members take up poisonous snakes visits town with a truck full of them. When Harriet catches a glimpse of a cobra, she remembers her ‘Rikki-Tikki-Tavi’ and is like:

Will Harriet solve Robin’s murder and exact justice? Or will she compound her family’s tragedy? I’m not going to give it away. But Harriet learns several things on her journey. There’s a seedy underside of her town and maybe she’s out of her depth to handle it. She’s taken the love and support of people around her for granted, particularly the family maid, Ida. And she has a rude awakening that when times get tough, you can’t just cut through them easily, like:

I had no idea what to expect when I started reading ‘A Little Friend.’ I wondered if it would be anything like ‘The Secret History.’ While I didn’t see many similarities between Tartt’s first novel and her follow-up (there are no dark academia vibes here), I was surprised to find echoes of Charles Portis’s classic ‘True Grit.’ (You may remember that Tartt wrote a glowing afterword for the edition I reviewed.) Tartt’s rendering of the premise, where a young girl is out to avenge a loved one’s murder, feels more gritty and dangerous. Harriet is a little less worldly and experienced than Portis’s protagonist, Mattie Ross, and her missteps have further-reaching consequences. I’ll enjoy comparing and contrasting the two in my mind for a while. I’ll also think about how Tartt depicts race and class dynamics in the Deep South. Several of the characters are flat-out bigots, using slurs or shooting guns at Black people for laughs. Others are the more subtle kind. In one example, Ida is required to drink out of her own glass, not from one the family uses. And Harriet’s assessment of Danny’s guilt originates in her disdain for his class. Because he’s a felon from a bad family, she’s like:

In the end, I have mixed feelings about ‘The Little Friend.’ I thought the premise was interesting, and I was invested in Harriet’s journey, but the story dragged. Despite having moments of riveting intensity, particularly when the snakes are involved, I thought this book could have been a lot shorter. I’m glad I read it, but it won’t be in my top reads at the end of the year.

How it begins:

For the rest of her life, Charlotte Cleve would blame herself for her son’s death because she had decided to have the Mother’s Day dinner at six in the evening instead of at noon, after church, which is when the Cleves usually had it. Dissatisfaction had been expressed by the elder Cleves at the new arrangement; and while this mainly had to do with suspicion of innovation, on principle, Charlotte felt that she should have paid attention to the undercurrent of grumbling, that it had been a slight but ominous warning of what was to come; a warning which, though obscure even in hindsight, was perhaps as good as any we can ever hope to receive in this life.

Though the Cleves loved to recount among themselves even the minor events of their family history—repeating word for word, with stylized narrative and rhetorical interruptions, entire death-bed scenes, or marriage proposals that had occurred a hundred years before—the events of this terrible Mother’s Day were never discussed. They were not discussed even in covert groups of two, brought together by a long car trip or by insomnia in a late-night kitchen; and this was unusual, because these family discussions were how the Cleves made sense of the world. Even the cruelest and most random disasters—the death, by fire, of one of Charlottes’s infant cousins; the hunting accident in which Charlotte’s uncle had died while she was still in grammar school—were constantly rehearsed among them, her grandmother’s gentle voice and her mother’s stern one merging harmoniously with her grandfather’s baritone and the babble of her aunts, and certain ornamental bits, improvised by daring soloists, eagerly seized upon and elaborated by the chorus, until finally, by group effort, they arrived together at a single song; a song which was then memorized, and sung by the entire company again and again, which slowly eroded memory and came to take the place of truth: the angry fireman, failing in his efforts to resuscitate the tiny body, transmuted sweetly into a weeping one; the moping bird dog, puzzled for several weeks by her master’s death, recast as the grief-stricken Queenie of family legend, who searched relentlessly for her beloved throughout the house and howled, inconsolable, in her pen all night; who barked in joyous welcome whenever the dear ghost approached in the yard, a ghost that only she could perceive. “Dogs can see things that we can’t,” Charlotte’s aunt Tat always intoned, on cue, at the proper moment in the story. She was something of a mystic and the ghost was her innovation.

But Robin: their dear little Robs. More than ten years later, his death remained an agony; there was no glossing any detail; its horror was not subject to repair or permutation by any of the narrative devices that the Cleves knew. And—since this willful amnesia had kept Robin’s death from being translated into that sweet old family vernacular which smoothed even the bitterest mysteries into comfortable, comprehensible form—the memory of that day’s events had a chaotic, fragmented quality, bright mirror-shards of nightmare which flared at the smell of wisteria, the creaking of a clothes-line, a certain stormy cast of spring light.

Who they thanked:

In her acknowledgements, Donna Tartt thanks a bunch of people for helping her with the book, but one in particular is worth noting. Someone named Matthew Johnson is thanked for answering her questions ‘about the poisonous reptiles and muscle cars of Mississippi.’ An expert on poisonous reptiles and muscle cars seems like a pretty rad dude.

My rating:

‘The Little Friend’ by Donna Tartt was published by Bloomsbury Publishing in 2002 and 2005. 555 pages. $17 at Strand Book Store.

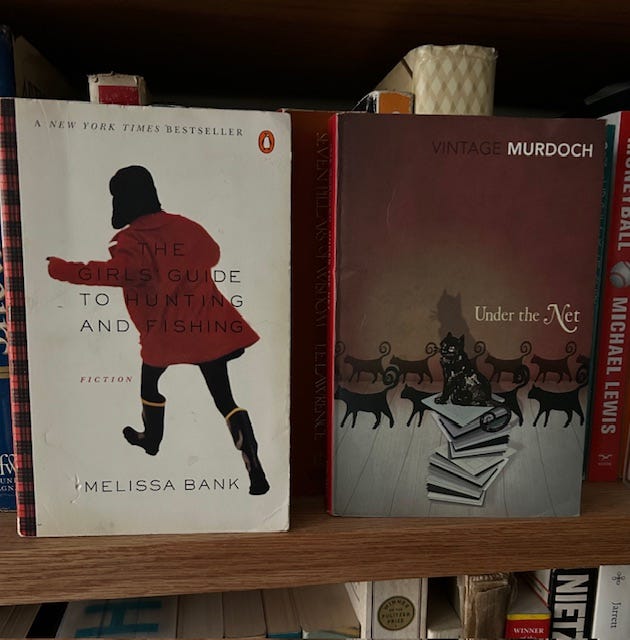

Recent pickups:

‘The Girls’ Guide to Hunting and Fishing’ by Melissa Bank (Womb House Books)

‘Under the Net’ by Iris Murdoch (Strand Book Store)

Books on GIF does not solicit review copies. We feature books we purchase at independent bookstores around New York City and on our travels, or were borrowed electronically from the Brooklyn Public Library.

What’s next:

Before you go:

ICYMI: Review #223

Read this: You all know I love to read author acknowledgements, so I enjoyed this piece in Literary Hub, ‘An Ode to Acknowledgements.’ I was glad to see that writer Sarah Wheeler, like me, always reads the acknowledgements first. I encourage you to do the same. So many good details can be found in them! Hat tip to

, who writes the Reading Under the Radar newsletter, for the link.Read this, too: Cassie also organized a great newsletter that pulls together the most anticipated 2024 reads from several book-related newsletter writers. So many great books in there, including the one I’m most excited for. Check out the list!

Thanks for the shoutout! Fellow newsletter writer

included Books on GIF in her list of ‘10 Cool Newsletters I’ll Be Reading In 2024.’ I get several of these newsletters as well and can confirm they are cool. Check them out!

Thanks for reading, and thanks especially to Donna for editing this newsletter!

Until next time,

MPV

I've been waiting for this one - the alert just came through on my phone and I literally said "fuck yes" out loud in the very busy coffee shop lol.

I've been about 70% done with The Little Friend for about two years now. I thought I was missing something - there are moments of brilliance and Goldfinch-ness but otherwise so much drag, and its hard to drag me. I am encouraged to finish it though now that you failed to spoil the ending.

Giphys were slapping today too.

Great piece. I read it when it came out and definitely thought it needed editing. Looking back on it, the only thing I can remember is the significance of a huge water tower...what was that about? In general US editors seem to be terrified of editing these bestselling literary novelists: Tartt, DeLillo, Franzen would all be massively improved by a spot of judicious pruning. So lucky that Strout, Pratchett and Tyler seem happy to write short books!

I have also picked up Under the Net in the last week. But it's a struggle, and I found myself yesterday completely distracted by Strout's Anything is Possible, which I consumed, or inhaled, in two hours. Bliss.