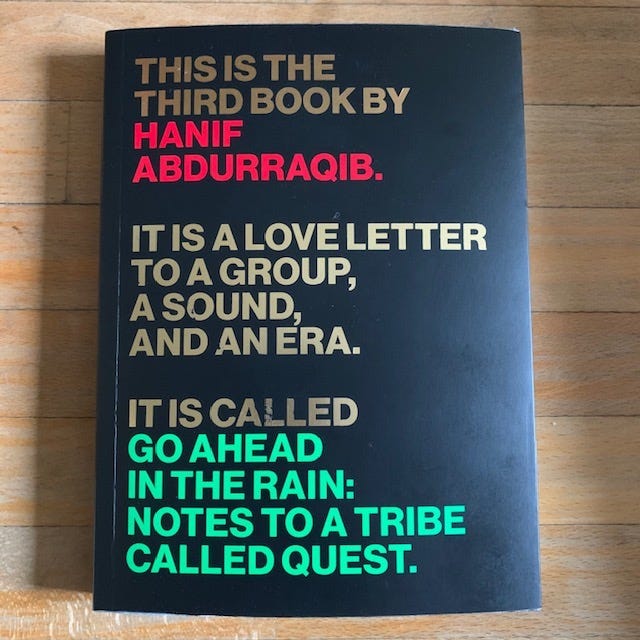

I can’t remember the last time a book seemed to transport me literally through space and time, but I was taken back to my senior year of high school in 1993 by this Sunday’s selection, ‘Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest’ by Hanif Abdurraqib:

Back then, I listened to a lot of rap music, particularly driving around my hometown, White Plains, in my Army green 1969 Plymouth. Brian or Armand or Wolf would be in the passenger seat controlling the tape deck, deciding whether we listened to a mixtape from Doo Wop and the Bounce Squad, or something dubbed off WBAI’s ‘Underground Railroad’ show, or new releases from Public Enemy, Wu-Tang Clan, Black Moon, Nas, or, more often than not:

Tribe’s second album, ‘The Low End Theory,’ was always in heavy rotation. And I have a hazy memory of when I heard Tribe’s third album, ‘Midnight Marauders,’ for the first time after it was released in late 1993. Brian and I drove down Central Avenue to Nobody Beats the Wiz in Yonkers to get it most likely, and then we probably cruised around lower Westchester listening to it. Here’s a reenactment of us enjoying ‘Award Tour’:

I remember that we both thought the album was something special; completely new and original, as if it came to us from the future where music was more sophisticated and awesome. Thanks to poet and essayist Hanif Abdurraqib’s 206-page love letter to Tribe and to that era, I was able to relive this moment where I heard great music for the first time with my best friend. It made me experience the meaning of this Japanese word:

Most writing about music is bad, and I hate it. It just doesn’t work when a music critic tries to describe what a song sounds like. And when songs are mentioned in a novel, it feels awkward. It makes me crazy when Haruki Murakami does this; it feels like he’s doing more to show off his musical taste than to advance the story. The only writers I’ve found who understand how to write about music are Lester Bangs and Hanif Abdurraqib, because they get it. They understand that the way to write about music is to hardly write about it at all, to focus instead on the emotions and memories songs evoke, and to connect music to moments that are bigger than the songs themselves. Abdurraqib does this brilliantly and beautifully in ‘Go Ahead in the Rain.’ The book traces A Tribe Called Quest’s lineage, and that of rap music generally, back through the history of the black experience in America starting with slavery, as you’ll see in the excerpt below. Also contained here is the backstory about how Q-Tip, Phife, Ali Shaheed Muhammad and Jarobi came together, how they crafted their three iconic albums, how things started to fall apart on the two albums before their breakup, and how they reunited for one last hurrah before tragedy struck. Woven in are Abdurraqib’s personal recollections of first encountering and falling in love with Tribe’s music, often told as letters written to members of the group. The book also includes fascinating details and haunting anecdotes from history and current events. The origin story of Jet magazine is included here. As is a retelling of the police shooting of Alton Sterling, a black man who sold CDs outside a grocery store in Louisiana. There’s also the story about the love between Leonard Cohen and Marianne, who inspired several of his songs. Trump’s election appears, too. In his back-cover blurb, writer Rembert Browne describes best how Abdurraqib connects all these disparate elements: ‘Go Ahead in the Rain reminds anyone fortunate enough to receive its pages that being black in America is to be part of a lineage, that no one person’s story exists in a vacuum, and that, like Hanif with Phife and Ali and Q and Jarobi, connective tissue exists all around us, invisible to the indifferent and brightly illuminated to the curious.’ I learned so much from this book. For example, I never knew that Phife’s mother was a poet. It was a treat to read her work here. Also, I never knew how Otis Redding died. I will be thinking about how a member of the Bar-Kays, who was the sole survivor of the plane crash into a lake that killed Redding and his other bandmates, could only watch, clinging to a seat cushion and unable to swim, as the wreckage pulled them beneath the waves. Thinking about that again, I’m like:

‘Go Ahead in the Rain’ had been on my reading list for a while, but I didn’t pick it up until I visited Nate, one of my best friends from college, in Cincinnati right before Christmas. Nate and I connected over A Tribe Called Quest and early 90s hip-hop when we first met in the dorm, and he had the book on the nightstand in his guest bedroom. I took that as a cosmic sign, so I went on an excursion to the local indie book store up the street from his house and bought it. It’s a wonderful book. It’s an ode to a great band that may be a little too loving and uncritical. But, more importantly, it reminds us how music connects us to friends, to memories and to history. You should all read this book.

How it begins:

In the beginning, from somewhere south of anywhere I come from, lips pressed the edge of a horn, and a horn was blown. In the beginning before the beginning, there were drums, and hymns, and a people carried here from another here, and a language stripped and a new one learned, with the songs to go with it. When slaves were carried to America, stolen from places like West Africa and the greater Congo River, with them came a musical tradition. The tradition, generally rooted in one-line melodies and call-and-response, existed to allow the rhythms within the music to reflect African speech patterns—in part so that everyone who had a voice could join in on the music making, which made music a community act instead of an exclusive one.

Once in America, where the slaves were sent to work in America’s South, this ethos was blended with the harmonic style of the Baptist church. Black slaves learned hymns, blended them with their own musical stylings that had been passed down through generations, and thus, the spiritual was born. In the early nineteenth century, free black musicians began picking up and playing European stringed instruments, particularly violin. It started as a joke—to mimic European dance music during black cakewalk dances. But even the mimicry sounded sweet, and so the children of slaves made what sweet sounds they could and stole a small and precious thing after having a large and precious history stolen from them.

But before this, when slaves were first brought to North America in the early 1600s, slaves from the West African coast would use drums to communicate with each other, sending rhythmic messages that could not be decoded by Europeans. In this way, slaves, whose family members were often held captive in different spaces, could still enter into distant but meaningful conversations with one another. In 1740, the slave codes were enacted, first in South Carolina. Among other things, drums were outlawed for all slaves. Slave Code of South Carolina, Article 36 reads: “And … it is absolutely necessary to the safety of this Province, that all due care be taken to restrain … Negroes and other slaves … [from the] using or keeping of drums, horns, or other loud instruments, which may call together or give sign or notice to one another of their wicked designs and purposes.”

My rating:

‘Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest’ by Hanif Abdurraqib was published by University of Texas Press in 2019. 206 pages. $16.95 at Joseph-Beth Booksellers in Cincinnati, Ohio.

More things worth your time:

Read this: The Guardian has an interesting piece about how Amazon tracks what you’re reading, when you’re reading, and for how long, on its Kindle devices.

Read this, too: This weekend, I flipped through some recent editions of the New York Times Book Review and came across this interview with Phoebe Waller-Bridge. I love her quote: ‘Looking back, I started out feeling reading was an escape, then a chore, then a habit, then a luxury. Only now I’ve realized what a necessity it is, and how easily it’s taken for granted.’ And I also read this interview with Laurie Anderson. In it, she says: ‘Books are the way the dead talk to the living.’

Do this: Strand Book Store is hosting a panel discussion on the life of Zora Neale Hurston on Feb. 24 at 7 p.m. to coincide with the new release of two of her works: ‘I Love Myself When I am Laughing’ and ‘Hitting a Straight Lick.’ The panel features Rachel Cargle, Mahogany L. Browne, Morgan Jerkins and Jamia Wilson. Click here for more information.

In two weeks you’ll get a review of ‘Barracoon’ by Zora Neale Hurston. Also in the queue are ‘My Sister, the Serial Killer’ by Oyinkan Braithwaite, ‘The Book of X’ by Sarah Rose Etter and ‘Killers of the Flower Moon’ by David Grann, among others.

In case you missed it: Books on GIF #124 featured ‘The Great Believers’ by Rebecca Makkai.

Shoot me an email if there’s a bestseller, a classic or a forgotten gem you want reviewed.

Please click the heart button above if you enjoyed this newsletter. You can also share it with a friend:

Follow me on Twitter and Instagram.

Thanks for reading, and thanks especially to Donna for editing this newsletter!

Until next time,

MPV