'Almanac of the Dead' by Leslie Marmon Silko

'Here was the new work of the Destroyers; here was destruction and poison. Here was where life ended.'—Review #152

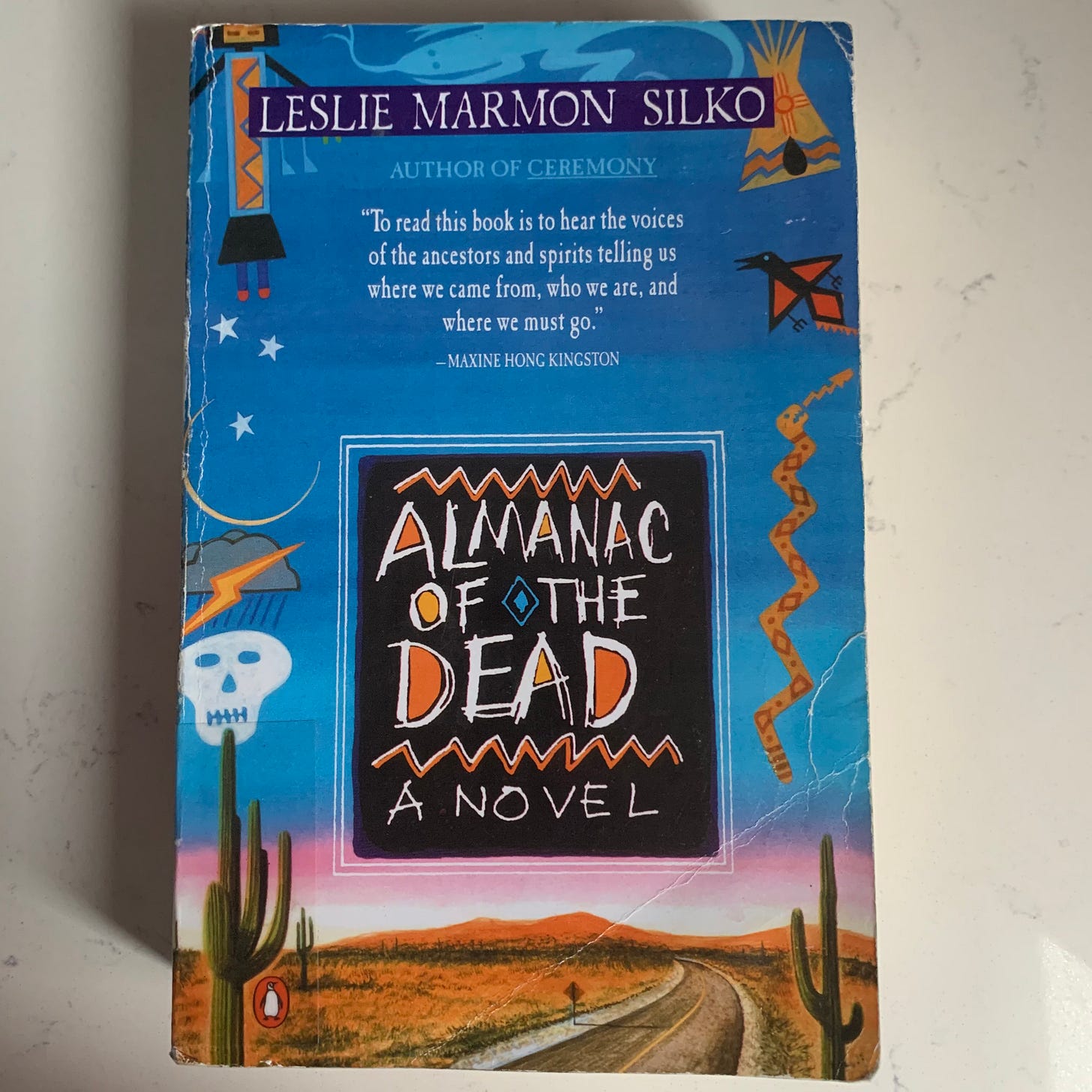

I had never heard of this novel or its author until I saw this Instagram post from the Strand Book Store on Indigenous People’s Day last year. I had been wanting to read more indigenous authors, and I was intrigued by both the title and the extremely 1990s cover design. Take a look:

If you enjoy this review, click the ♥️ above or

New here?

So I searched online. I don’t remember why I went to Alibris over the Strand, but the copy I purchased was being discarded by the Pima County Public Library. I had to look up were that is, and I learned that Pima County encompasses Tucson, Ariz., which is a primary location in the book. Clearly this was meant to be, right?

Leslie Marmon Silko is a poet and novelist who I learned from this bio has Native American, Mexican and European heritage, and who grew up on the Pueblo Laguna reservation near Albuquerque. Silko spent 10 years writing ‘Almanac of the Dead,’ which was first published in 1991 and was funded through a MacArthur ‘genius’ award. The result is a wonderfully and disturbingly complex and fascinating epic novel that I will be thinking about, and be haunted by, for a while. It’s a hard book to describe. The main character isn’t a person, but an energy: the intense and lingering rage of indigenous peoples awaiting a long-overdue reckoning with the legacy of colonialism, slavery and genocide that occurred in the Americas. Because:

The energy is channeled through an accumulation of short chapters that jump around through time and place and include an ever-broadening and increasingly seedy cast of characters. It starts with Sterling, a middle-aged former railroad worker who’s been banished from his reservation for failing to prevent a Hollywood crew from filming a sacred site. He ends up in Tucson at the same time as Seese, a cocaine-addled ex-stripper who’s searching for her kidnapped infant son. She has seen on a daytime television program a woman named Lecha who uses ancient magical powers to locate the missing and the dead. Sterling and Seese eventually come to live on Lecha’s ranch, where Lecha lives with her twin sister, Zeta, and her drug- and gun-running son, Ferro. Sterling becomes a hired hand and Seese becomes a nurse and a secretary helping Lecha translate an ancient document. From there we are introduced to more characters on both sides of the Mexican-U.S. border who are involved in an array of bizarre and macabre dealings. There’s Trigg, who’s paralyzed below the waist and pressing homeless men into service of his developing blood-donation and organ-harvesting business. There’s Menardo, a Mexican insurance company owner who’s becoming increasingly paranoid and delusional as unrest grows in Chiapas. There’s Beaufrey, the drug-dealing homosexual sadist who’s involved in eugenics and snuff films. There’s Tacho, Menardo’s driver, who gets messages from spirits in the form of macaws. There’s Angelita, a Marxist putting together an army of indigenous people to take back stolen land. There’s Rambo, who’s building an army of homeless Vietnam vets. There’s Max, a retired mob assassin who golfs several times a day. His wife, Leah, invests in real estate and wants to recreate Venice in the Arizona desert. (There are many others, like the Barefoot Hopi and even the historical Geronimo, but these few give you the gist.) What we learn from all the depravity, violence, drugs, sex and death in these characters’ lives is that the often-ignored legacy of colonialism and slavery in the United States, as well as in Central and South America, continues to weigh on our collective soul, and if left unresolved, will undo us all. This may sound confusing but:

Even though this book came out 30 years ago, it speaks to the current moment. You could argue it predicts much of the political turmoil we’ve seen in recent months, from people taking to the streets to protest injustice, to a renewed focus on how we’ve harmed the environment, to what appears to be many people suffering a collective break from reality. It’s not for every reader, though. It ticks just about every trigger warning you can think of, and I think its portrayal of gay men as mostly perverts and sadists is problematic. Even so, I appreciated being challenged by the story and its message, and I enjoyed Silko’s writing. Overall, ‘Almanac of the Dead’ has a very ’90s indie vibe; I could almost hear ‘Reservoir Dogs’ or ‘Rage Against the Machine’ playing in the background while I read. I’m glad the Strand surfaced this book into my Instagram feed, but I’m surprised I haven’t seen it recommended more often. This remarkable book should be part of our ongoing conversation about race and justice in the U.S. I recommend it.

How it begins:

The old woman stands at the stove stirring the simmering brown liquid with great concentration. Occasionally Zeta smiles as she stares into the big blue enamel pot. She glances up through the rising veil of steam at the young blond woman pouring pills from brown plastic prescription vials.

Another old woman in a wheelchair at the table stares at the pills Seese counts out. Lecha leans forward in the wheelchair as Seese fills the syringe. Lecha calls Seese her “nurse” if doctors or police ask questions about the injections or drugs. Zeta lifts the edge of a sleeve to test the saturation of the dye. “The color of dried blood. Old blood,” Lecha says, but Zeta has never cared what Lecha or anyone else thought. Lecha is just the same.

Lecha abandoned Ferro, her son, in Zeta’s kitchen when he was a week old. “The old blood, old dried-up blood,” Ferro says, looking at Lecha, “the old, and the new blood.”

Ferro is cleaning pistols and carbines with Paulie at the other end of the long table. Ferro hates Lecha above all others. “Shriveled up,” he says, but Lecha is concentrating on finding a good vein for Seese to inject the early-evening Demerol.

My rating:

‘Almanac of the Dead’ by Leslie Marmon Silko was published by Simon & Schuster Inc. in 1991 and by Penguin Books in 1992. 763 pages. It’s out of stock at BookShop.org, but there is one copy left at Strand Book Store for $23.

Disagree with my review? Let me know:

Connect: Twitter | Instagram | Goodreads | Email

Before you go:

ICYMI: Review #151 featured ‘Milkman’ by Anna Burns. | Browse the Archive

Read this: Donna and I recently watched Pixar’s ‘Soul.’ Other than attacking my beloved Knicks, it didn’t leave a lasting imprint on me. But this piece by Namwali Serpell in The New Yorker called ‘Pixar’s Troubled “Soul”’ offers a fascinating and enlightening look at the film’s ‘elision’ (I love that word) of ‘what soul means to black culture.’

Read this, too: You may have heard that there are people who organize bookshelves by color. Well, according to the Seattle Times, this new book store in Seattle organizes books by emotions.

Cook this: BoG friend Rad Dishes offers ‘A Tale of Two Paneers’ in this month’s newsletter. I am excited to try these recipes. They could be a far, far better thing to cook than I have ever cooked.

Thanks for reading, and thanks especially to Donna for editing this newsletter!

Until next time,

MPV