'The Road' by Cormac McCarthy

'People were always getting ready for tomorrow. I didn't believe in that. Tomorrow wasn't getting ready for them.' — Review #143

I wasn’t due to send a newsletter for another week, but Cormac McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel is so intense that I finished it quickly, and I figured why not send my review early. I flew through it like:

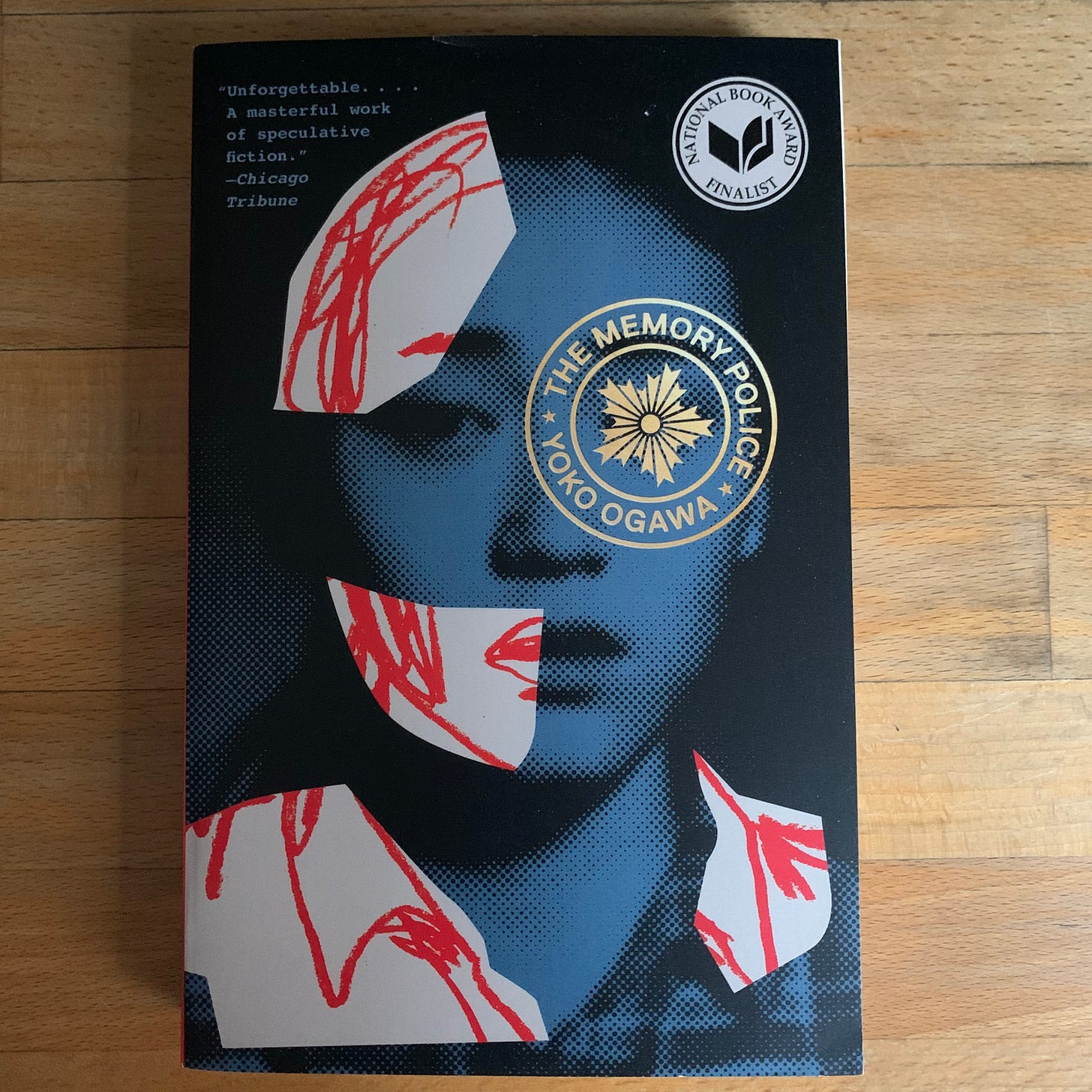

Here’s a better look at the cover:

If you enjoy this review, click the ♥️ above or

A man and his son, both unnamed, are on a journey south to the coast through a post-apocalyptic hellscape that appears to once have been North America. The country is barren and scorched. It’s cold, the wind carries ash, and the sky is always gray. There seem to be no animals left alive. Very few plants, too. Abandoned vehicles litter the road. There’s an occasional corpse. The people who survived whatever disaster befell the Earth—whether it’s war or environmental calamity or the Rapture (the reason doesn’t matter)—have been reduced to scrounging for whatever canned goods remain from the before times. Some people have become cannibals. Where the man and boy are going specifically is as unclear as where they came from, but it’s important that they must keep pushing forward with their shopping cart of their meager provisions and gear (mostly blankets and a revolver that’s low on bullets). They frequently have to hide to avoid the ‘bad’ people along the road who would rob them, and likely kill and consume them. They also explore abandoned homes, grocery stores and roadside gas stations looking for things to eat, tools to use, or, as seen in this GIF from the 2009 film adaptation starring Viggo Mortensen, implements to make fire to ward off the relentless cold and darkness:

There are moments of true terror and horror. There’s a scene where they explore a mansion and pry up a padlocked trap door in the floor to see if useful supplies are hidden there. I’ve been thinking about what they found for several days. And then when the man explores a capsized yacht and had to leave the boy on the shore: The tension almost gave me heart palpitations. But there also are rare moments of joy and even grace. I like the scene where the father rummages through a vending machine and finds one last unopened can of soda. He offers it to the boy, who has no memory of soft drinks, so he can have a brief experience of comfort and sweetness. There also is the scene where they find a backyard bunker filled with canned goods, and even bacon and coffee. Could you imagine how good a cup of coffee, even years-old instant, would taste after the apocalypse? And bacon? I’d be like:

I’m a sucker for novels where the author bends the rules of grammar or composition to convey subtle points about the story. Like Bernardine Evaristo’s ‘Girl, Woman, Other,’ McCarthy strips out quote marks around speech. He also removes apostrophes from some contractions like cant and dont. This mirrors a world that’s been pillaged and nearly picked clean. The sentences are brief, and there are minimal metaphorical adornments, because when there’s hardly anyone left on Earth:

‘The Road’ is best understood as a Sunday-school parable about good and evil. The boy is concerned about whether he and his father are the ‘good guys’ and different from the murderous cannibals out there. They are the good guys, the father assures him, but when they are faced with choices about whether to do good acts and help others, the man always opts for self-preservation, hoarding resources or running away. The boy, however, wants to help. He feels guilt about running away from what they found padlocked in that basement. He offers food to an old man they meet on the road, and begs his father not to shoot another man who has robbed them. The book seems to suggest that these deeds are being tallied: At the end of life’s road, we will face death or salvation, and the choices we make along the way will determine which we get. This is fine. I also believe in:

I thought McCarthy missed opportunities to include more dramatic moral dilemmas to really explore the nature of good and evil. For example, the man teaches the boy how to use the gun to commit suicide should the bad people close in. But that circumstance never really manifests, and the potential for an interesting and literal use of the ‘Chekhov’s gun’ principle was wasted. Not to be macabre, but it would have been interesting to see either father or son faced with the choice to pull the trigger to save the other, or themselves, from a horrible fate. This, plus the deus ex machina ending, which I won’t give away, felt like a cop out. Still, this is an intense book, and I enjoyed reading it. Some have found it uplifting. I recommend it.

How it begins:

When he woke in the woods in the dark and the cold of the night he’d reach out to touch the child sleeping beside him. Nights dark beyond darkness and the days more gray each one than what had gone before. Like the onset of some cold glaucoma dimming away the world. His hand rose and fell softly with each precious breath. He pushed away the plastic tarpaulin and raised himself in the stinking robes and blankets and looked toward the east for any light but there was none. In the dream from which he’d wakened he had wandered in a cave where the child led him by the hand. Their light playing over the wet flowstone walls. Like pilgrims in a fable swallowed up and lost among the inward parts of some granitic beast. Deep stone flues where the water dripped and sang. Tolling in the silence the minutes of the earth and the hours of the days of it and the years without cease. Until they stood in a great stone room where lay a black and ancient lake. And on the far shore a creature that raised its dripping mouth from the rimstone pool and stared into the light with eyes dead white and sightless as the eggs of spiders. It swung its head low over the water as if to take the scent of what it could not see. Crouching there pale and naked and translucent, its alabaster bones cast up in shadow on the rocks behind it. Its bowels, its beating heart. The brain that pulsed in a dull glass bell. It swung its head from side to side and then gave out a low moan and turned and lurched away and loped soundlessly into the dark.

My rating:

‘The Road’ by Cormac McCarthy was published by Vintage Books in 2006. 287 pages. $14.72 at Bookshop.org.

Disagree with my review? Let me know:

Up next:

Review #142: ‘wow, no thank you.’ by Samantha Irby

Support BoG: Twitter | Instagram | Goodreads

Contact me: booksongif@gmail.com.

Before you go:

Read this: ‘Mango Son Theen’ by Jasmine Sawers in Jellyfish Review is a short story set in Thailand that imagines cultural-imperialist origins of the name for the ‘Queen of Fruits,’ the mangosteen. It’s a good read.

Do this: The virtual Brooklyn Book Festival continues today. Here’s the full lineup of events.

Thanks for reading, and thanks especially to Donna for editing this newsletter!

Until next time,

MPV

Review #143 used GIFs by @idealist and others from Giphy.com.

Books on GIF newsletters with most ♥️s

One of McCarthy's briefest and bleakest. It doesn't hold a candle to Blood Meridian though, in my humble opinion.

V excited to read this after the apocalypse is over and I can handle it.