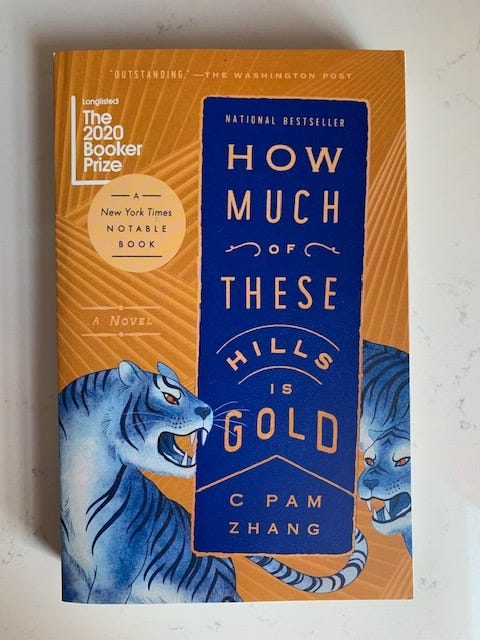

'How Much of These Hills Is Gold' by C Pam Zhang

'What makes a home a home? Tell me a story I can dream on.'—Review #167

C Pam Zhang’s debut novel includes a page with only this statement: ‘This land is not your land.’ It comes after pages of praise for the book, which was longlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize, among other accolades, and before the table of contents. What does it mean? Whom is it for? To what land is it referring? And how does it relate to the story? I’ve puzzled over the line since I finished ‘How Much of These Hills Is Gold.’ But first, a quick recap.

Here’s the cover:

Click ♥️ if you enjoy this review. ⬆️

The novel is set in an unidentified western frontier in the years during and following a gold rush. Lucy and Sam are tween siblings who need silver coins to conduct a proper burial for their recently deceased father, Ba. Their mother, an immigrant from Asia, probably China, called Ma, vanished years ago. Sam has Ba’s gun and tries to hold up a bank in their hardscrabble mining town for the silver. That fails, so Lucy and Sam steal a horse, pack their father’s corpse into a trunk and escape into the wilderness. They roam for weeks, searching for silver and the perfect burial spot. On their journey, they contend not only with the stink of their decomposing father, and the flies he attracts, but also with creepy men, grief, bitter memories and racism. Though Lucy and Sam were both native to the story’s location, they are consistently treated as foreigners by the whites they encounter because of their Asian heritage. And though Lucy and Sam were born female, Sam, who was treated by Ba like a son and who identifies as male, sheds the remnants of a feminine identity and lives as a boy. One day after their father is finally buried, Sam joins traveling frontiersmen and vanishes. We follow only Lucy then, who finds menial work in a town and as a companion for a rich white girl. The story then jumps back in time to before Ba’s death and Ma’s disappearance, when the family was together. We see Ma arrive from across the ocean with other immigrants who are pressed into building railroads or digging for gold or other resources like:

We see the family try to scrape a living from the ground, the experiences embellished by phrases in Ma’s native language. They move from village to village in search of mining work and a place to call home. At every turn they face discrimination and racism. In one mining village, they are forced to live in a former chicken coop. Eventually, Ba finds gold, and he and Sam take clandestine missions to gather it without arousing suspicions. Gold is the dream and the answer, it means freedom, respect and agency. It provides the means to escape the chicken coop, to buy land and to have a:

We learn that Ba has a secret and a hidden shame with tragic consequences. The family’s dreams are shattered by jealousy, desperation, bad weather and hate. The story then jumps forward in time to when Lucy and Sam are nearly adults and are reunited. So how does this connect to ‘This land is not your land’? My first thought was that it was an admonishment of white people like those depicted in the book who claim to be the only authentic Americans and who view Asian Americans as inherently foreign. I thought it also could be a statement that no one has the right to claim land, or perhaps that only indigenous people have that right. Or, it could be a warning to immigrants that there are people who don’t want them here and will make them feel like strangers. And I thought it could be a reference to the land itself, and how we’ve plundered gold and other materials from the ground and done violence to the planet and the climate. It could mean all of these things or none of them. But I’m going to chew on it like:

‘How Much of These Hills Is Gold’ is a quick read. Zhang, who was born in Beijing but describes herself as ‘mostly an artifact from the United States,’ has a sharp writing style that moves the story along, sometimes too quickly. I often felt disoriented and confused about what was happening or where characters were in the timeline. Maybe that was intentional, to reflect Lucy’s and Sam’s experiences as unmoored children. But at times it felt rushed, particularly near the end. I also think the story followed the less interesting character. I would have preferred to follow Sam’s adventures. Even so, ‘How Much of These Hills Is Gold’ is an important story about identity and visibility. I didn’t love this book, but I’m glad it exists and that I read it.

How it begins:

Ba dies in the night, prompting them to seek two silver dollars.

Sam’s tapping an angry beat come morning, but Lucy, before they go, feels a need to speak. Silence weighs harder on her, pushes till she gives way.

“Sorry,” she says to Ba in his bed. The sheet that tucks him is the only clean stretch in this dim and dusty shack, every surface black with coal. Ba didn’t heed the mess while living and in death his mean squint goes right past it. Past Lucy. Straight to Sam. Sam the favorite, round bundle of impatience circling the doorway in too-big boots. Sam clung to Ba’s every word while living and now won’t meet the man’s gaze. That’s when it hits Lucy: Ba is really gone.

She digs a bare toe into dirt floor, rooting for words to make Sam listen. To spread benediction over years of hurt. Dust hangs ghostly in the light from the lone window. No wind to stir it.

My rating:

‘How Much of These Hills Is Gold’ by C Pam Zhang was published in 2020 and 2021 by Riverhead Books. 320 pages. $14.72 at Bookshop.org.

Let’s discuss:

What do you think Zhang means when she writes ‘This land is not your land’? Leave a comment.

What’s next?

Share Books on GIF with a friend.

Before you go:

ICYMI: Review #166 featured ‘The Transit of Venus’ by Shirley Hazzard | Browse the Archive

Read this: Maybe you can help me. I’ve read through this piece in BookForum about animated GIFs twice, and I don’t understand what it’s trying to say. Is it attacking GIFs? Attempting to understand them as an emerging art form? I did understand this sequence, though:

Like the photograph, which clips a moment out of time and uses it to say this is how things looked in this moment, the GIF has captured how it was that we moved in that moment. It liberates motion itself from time and elevates it to a mythology of movement; and it’s in this technological middle space where we find ourselves, right now, able to write this captured motion but simultaneously experience it as art. It hasn’t yet fossilized, not completely, into language.

I would argue that GIFs are language, and we are experimenting with them as such in every issue of Books on GIF. Someone should tell BookForum, and this author, to subscribe!

Do this: Lauren Groff discusses her new novel ‘Matrix’ with writer Jia Tolentino at a virtual event on Fri., Sept. 10, at 7 p.m., organized by Books Are Magic in Brooklyn. Tickets range from $0 for access to the Zoom to $36.50 for the event plus a signed book. Click here for more information.

Thanks for reading, and thanks especially to Donna for editing this newsletter!

Until next time,

MPV

Have you read Because Internet? The Bookforum piece reminded me of it. It's written by a linguist who argues we should think of emojis as gestures — not a language. I really like that description.