3 from BoG: Random Books I Read This Summer

'The Education of Kendrick Perkins' by Kendrick Perkins with Seth Rogoff, 'Nietzsche in Italy' by Guy de Pourtalès and 'The Castle of Otranto' by Horace Walpole—Review #215

I’ve been all over the place this summer, both physically and in my reading. In June, Donna and I visited the Puglia region of Italy and stayed with friends in a city called Nardò. We ate great food (especially burrata), swam in the Ionian Sea and drank Aperol spritzes. It was glorious! Here’s the plaza in the old section of Nardò:

In August, we took a side quest to Dallas and Fort Worth, where we visited some more friends and where Donna had a work trip. We had a great time in Texas, though it was so windy and hot (110 degrees!) it felt like we were inside a hair dryer. We ate barbecue and saw lots of cool stuff, like these stuffed raccoons playing poker in Fort Worth:

You’ve already seen most of what I read this summer: books by Eva Baltasar, Fleur Jaeggy, Clarice Lispector, A.S. Byatt and Hernan Diaz. But I also fit random stories in between: A sports memoir, a biographical philosophy essay and a weird novel. I finished ‘The Education of Kendrick Perkins’ right before we boarded the plane to Italy. I read ‘Nietzsche in Italy’ on Italian beaches, and spotted ‘The Castle of Otranto’ in a bookstore days before seeing the castle itself. Here’s the roundup:

‘The Education of Kendrick Perkins: A Memoir’ by Kendrick Perkins with Seth Rogoff

'To know anything for real requires taking a chance, facing danger: the danger of trying to find out where we came from and who we are.'

Longtime Books on GIF readers know I’m a big fan of Seth Rogoff’s work. I’ve reviewed his novels ‘First, the Raven: A Preface’ and ‘Thin Rising Vapors,’ and linked to his short stories. After my newsletter on Chris Herring’s ‘Blood in the Garden,’ about my beloved 1990s New York Knicks, Rogoff emailed me about his book project with former NBA star and current ESPN basketball analyst Kendrick Perkins. I couldn’t believe it. A novelist I really enjoy working on a basketball book? And with Kendrick Perkins, an engaging TV personality? What a fascinating pairing! I was all in, like the guy in the ‘sickos’ meme:

Rogoff mentioned in his email that he and Perkins wanted to write a different kind of sports book. Although my knowledge of the genre is limited, I think they pulled it off. Perkins’s memoir includes important, and sometimes painful, moments from his life. It starts with his road trip from Texas to Boston after getting drafted in 2003 by the Celtics out of high school, and his adjustments to life in Beantown before winning an NBA championship there in 2008. He describes growing up in Beaumont, Texas, and being raised by hard-working grandparents after his single mother was murdered. He opens up about facing depression as his basketball career wound down, and then overcoming it to start a new life in broadcasting. The different element to this book is how Perkins contextualizes his experiences within the sweep of Black history and current events in the United States. In one example that stuck with me, he traces the history of The Pear Orchard, the Black neighborhood where he grew up in Beaumont, back to its foundation by former slaves after the Civil War. They acquired land and donated a parcel for a school that evolved over many decades into Ozen High School, where Perkins played ball and attracted NBA scouts. I love details like this, and I wanted more, particularly about his time in the NBA. But ‘The Education of Kendrick Perkins’ isn’t a salacious tell-all. It’s about a man who beat the odds to make it in the NBA and who wants to share what he learned along the way—information and experiences we could all benefit from knowing. A sports memoir is not a book I normally would have picked up, but I’m glad I did in this case. It’s worth checking out.

How it begins:

It was the middle of August 2003 when I left Beaumont, Texas. I was eighteen years old. My friend George Davis and I had decided to drive cross-country to Boston for the start of my NBA career with the Celtics. At the time, I had no way of knowing just how long this journey would be. In some ways, I’m still on the road.

I’d never lived outside Beaumont. Since I was five years old, I hadn’t lived anywhere but my grandparents’ house—a small, run-down shack on Glenwood Avenue painted yellow with green trim. That’s not to say I’d never left Beaumont. I’d traveled around the country to play ball, competing with the youth basketball elite for the attention of college and pro scouts. I’d played in the highest-level camps and tournaments. I’d banged and bruised with the biggest and most skilled players the amateur basketball world had to offer, guys like Dwight Howard and LeBron James.

But that wasn’t leaving Beaumont, that was taking Beaumont with me as I went in search of a fantasy—a fantasy dangled right before my eyes. Every player in every game I played in on those trips and in those elite camps thought he was going pro. Each guy dreamed of the NBA contract floating right there. He just needed to reach out, take a pen, and stroke a signature on the bottom and he’d be rich, famous, and set for life. When he opened his eyes, when he woke up in the morning after that sweetest of dreams, what was there? No pen. No paper. No money. Nothing. Just the same grinding poverty, and a day of hard work ahead.

My rating:

‘The Education of Kendrick Perkins: A Memoir’ by Kendrick Perkins with Seth Rogoff was published by St. Martin’s Press in 2023. 290 pages. $27.89 at Bookshop.org.

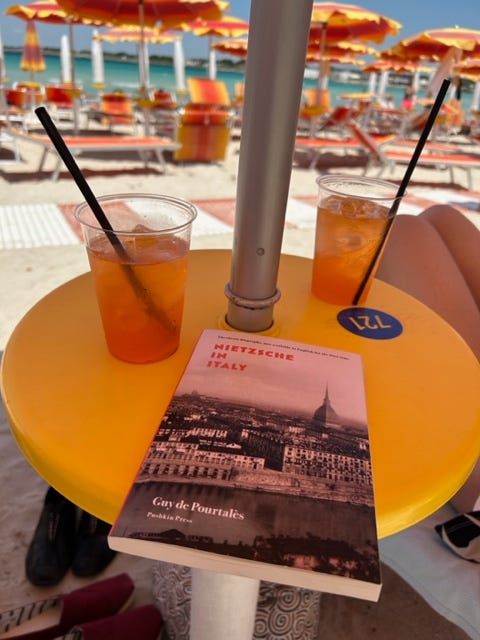

‘Nietzsche in Italy’ by Guy de Pourtalès

‘Then he makes his way back to his labourer’s room, exhausted but happy to have fired his weapons against Plato and against God.’

Friedrich Nietzsche changed my life, but that was a long time ago when I was in college and didn’t know any better. His writing about free thinking, the importance of awesome music and how we were all trapped in an eternal recurrence of the same from which only badasses unfettered by stuffy traditional values can be free was so exciting and inspiring when I was 20. I, too, was going to be a philosopher with a hammer! A smasher of history’s false idols! So I changed majors, and ransacked every used bookstore in Boston and wherever else I went for of books by or about him. Dude, I even bought a dusty, falling-apart French translation of ‘Thus Spoke Zarathustra’ at a market in Paris—and I can’t read French! I was way too into the 19th-century German philosopher. Thankfully, I grew out of this macho philosophy over the years. But I kept all the books (except that French one). I hadn’t thought much about ol’ Fred recently until I saw a review in The Wall Street Journal (subscription required) of Guy de Pourtalès’s nearly century-old biography of him that was recently, and for the first time, translated into English. I had to have it. And, for a minute, I felt like John Wick:

I took the book with me to Italy, because, of course, with its title, I had to. Here it is on the spiaggia di Sant'Isidoro between Aperol spritzes:

Pourtalès describes Nietzsche’s nomadic final years in Italy, which were a race against time to produce as much philosophical dynamite as he could before his eyes and his mind gave out. We see a sickly man, often bedridden by headaches, who’s far removed from any uber-being he may have created. He’s frustrated by unappreciated work and unrequited love. The scene where he is rejected by Russian intellectual Lou Andreas-Salomé is painfully awkward and sad. The disconnect was jarring between the man we see in ‘Nietzsche in Italy’ and the one conjured by the chest-thumping work I dimly remembered from college. Had I misunderstood him all along? Guy de Pourtalès took a hammer to one of my idols and forced me to see Nietzsche in a new light. His book-length essay is compelling and crisply written. I understand that it might not be for every reader, but if German philosophy is your thing, read this book.

How it begins:

Any being who observes a love they have lived with for a long time fading inside them calls to death for assistance. But death rarely responds to such a summons. So one must live, sadly; must survive. The wounded man raises himself, bandages his wound as best he can and takes flight. “Travel,” they urge him. So he departs with his shadow. Perhaps you will encounter him months or years later, healed. Apparently healed. But deep down, no one ever recovers from a withered love. He is not the same being that you once met. Yet it is him, his eyes, his smile, his hand. But he is enveloped in that “resounding solitude” of which Saint Jean de la Croix speaks, where his mute realities have taken on a quite different voice.

When in the autumn of 1876 Nietzsche set foot for the first time on Italian soil, he was fleeing his past. He tore his youth from his heart. This thirty-two-year-old man, brimming with still-intact spiritual power, had just made the first great sacrifice of his happiness. He renounced the secret love, the deep love which for more than six years had disturbed his life with a kind of hopeless intellectual dream, for Cosima Wagner. He was renouncing her illustrious husband, “the master” as all referred to him, the man of Bayreuth, whose apotheosis he had just witnessed in a theatre erected to his pride and who now appeared to Nietzsche—following this fall into popular glory—like some form of imposter, a simple showman of genius. He cleansed his soul from a protracted sickness in which he had indulged for years, a disease he had taken for strength, pure strength, but where he now discovered nothing more than coarse tufts and putrid vegetation. The young professor from the University of Basel left for a spell of convalescence to Genoa and Sorrento. For some time now, his sight had been seriously impaired. He suffered excruciating migraines. This slight intellectual, who shelters his gaze behind thick glasses and hides a gentle smile beneath an enormous moustache, first stops at the thermal baths of Bex, in the canton of Vaud, then, one mid-October evening in Geneva, boards the train for Italy.

My rating:

‘Nietzsche in Italy’ (Nietzsche en Italie) was originally published in 1929 by Bernard Grasset. Translated from the French by Will Stone and published by Pushkin Press in 2022. 126 pages, including notes and chronology. $15.76 at Bookshop.org.

‘The Castle of Otranto’ by Horace Walpole

‘Look, my lord! See heaven itself declares against your impious intentions!’

I was looking at the English section of a bookstore in Lecce, Italy, when I saw a copy of Horace Walpole’s ‘The Castle of Otranto.’ I hadn’t heard of the book or of Walpole before, but I knew a city named Otranto was nearby, so I filed it away in my brain. A few days later, I was in Otranto, standing in front of the castle:

There was an exhibit of Marc Chagall drawings inside, which Donna and I enjoyed. Atop the parapet, with its beautiful view of the Adriatic coast, I was reminded of the book I had seen earlier. I was like:

Alarm bells went off from the very first page of the introduction that says modern readers may find the book to be ‘by turns ludicrous and unreadable.’ Yikes! Equally concerning was the fact that the introduction seemed as long as the novel itself (never a good sign), and that I also had to sift through a ‘Note on the Text,’ a ‘Select Bibliography,’ a multi-page chronology of Horace Walpole’s life, two prefaces and a sonnet before reaching the first word of ‘The Castle of Otranto.’ It was as if the book was actively trying to discourage me from reading it. The bizarre story focuses on the antics of Manfred, prince of Otranto. Manfred’s son is killed on his wedding day by a massive helmet that falls from the sky. Crazed at the prospect of having no heir to his throne, Manfred decides he must divorce his wife and marry the young woman briefly betrothed to his son. This sets off a weird chain of events involving ghosts, talking paintings, sword fights, giant statues that fly into the sky and God’s wrath. This may all sound like exciting stuff, but it isn’t. The writing is plodding and overdone, with characters making long speeches instead of getting on with it. The introduction was right. Ludicrous and unreadable. I hate to say it, but skip this book.

How it begins:

Manfred, prince of Otranto, had one son and one daughter: the latter, a most beautiful virgin, aged eighteen, was called Matilda. Conrad, the son, was three years younger, a homely youth, sickly, and of no promising disposition; yet he was the darling of his father, who never showed any symptoms of affection to Matilda. Manfred had contracted a marriage for his son with the marquis of Vicenza’s daughter, Isabella; and she had already been delivered by her guardians into the hands of Manfred, that he might celebrate the wedding as soon as Conrad’s infirm state of health would permit. Manfred’s impatience for this ceremonial was remarked by his family and neighbours. The former, indeed, apprehending the severity of their prince’s disposition, did not dare to utter their surmises on this precipitation. Hippolita, his wife, an amiable lady, did sometimes venture to represent the danger of marrying their only son so early, considering his great youth, and greater infirmities; but she never received any other answer than reflections on her own sterility, who had given him but one heir. His tenants and subjects were less cautious in their discourses: they attributed this hasty wedding to the prince’s dread of seeing accomplished an ancient prophesy, which was said to have pronounced, That the castle and lordship of Otranto should pass from the present family, whenever the real owner should be grown too large to inhabit it. It was difficult to make any sense of this prophecy; and still less easy to conceive what it had to do with the marriage in question. Yet these mysteries, or contradictions, did not make the populace adhere the less to their opinion.

My rating:

‘The Castle of Otranto’ was published by Oxford University Press in 1982, 1998, 2008 and 2014. 132 pages, including two prefaces, notes and an appendix. $10.18 at Bookshop.org.

What’s next:

Before you go:

ICYMI: Review #214

Vote on this: I’ve got a few ideas for future installments of ‘3 from BoG,’ and I want to get your thoughts on them. The ideas are mostly self-explanatory, but here are two points of clarity: the short-story option includes fiction and nonfiction, and the series option includes one sci-fi, one fantasy and one romance novel that start a series.1 Please take a second to vote!

See this: Donna and I are very excited that a new bookstore has opened in our neighborhood, Lofty Pigeon Books. Check it out, and when you do, be sure to stop by the recommendations section, where you’ll see one from BoG:

If you enjoyed this review:

Thanks for reading, and thanks especially to Donna for editing this newsletter!

Until next time,

MPV

Newsletters you ♥️ the most

I’m thinking this would include opening books from the ‘Star Wars: Thrawn’ trilogy by Timothy Zahn, ‘The Wheel of Time’ series by Robert Jordan and the ‘A Court of Thorns and Roses’ series by Sarah J. Maas.

Can’t wait to read your review of Middlemarch. Are you a Magic Mountain fan? You inspired me to order both Diaz books.

Wow! I haven't heard anyone mention The Castle of Otranto in years! It was one of the books I had to read for a History of the English Novel class way back in my college days. Pretty sure I remember that it's considered the first gothic novel? Thanks for the blast from the past!