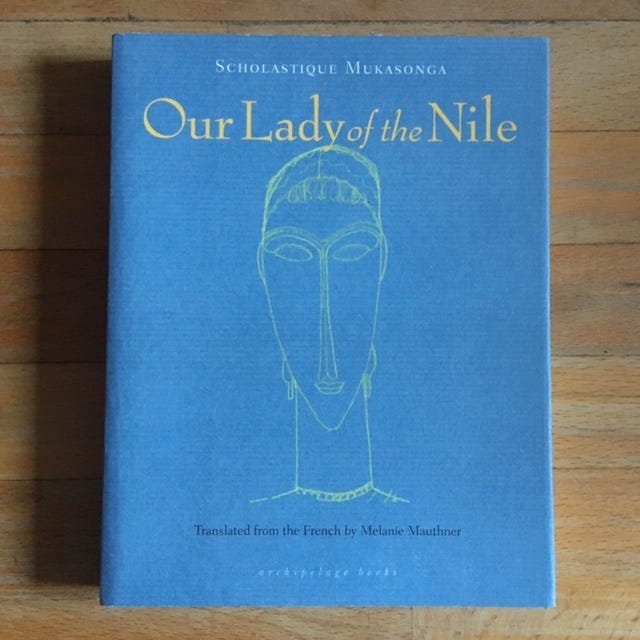

Welcome to the latest edition of Books on GIF, the animated alternative to boring book reviews. This Sunday's selection is ‘Our Lady of the Nile’ by Scholastique Mukasonga.

You all know that I try to diversify and enrich my reading life, and I’m abashed to admit that it seems I haven’t reviewed an African author since ‘Things Fall Apart’ by Chinua Achebe way back in issue #39. This won’t happen again, because if the wonderful and powerful literature of and from Africa isn’t featured prominently in your reading mix, then you’re doing this wrong. Beyond this week’s featured novel, which is set in Rwanda, look for a review of Somali writer Nuruddin Farah’s ‘Hiding in Plain Sight’ in the coming weeks, and for more going forward. I picked up ‘Our Lady of the Nile’ at the Strand after reading about Mukasonga’s work in a back issue of The New York Review of Books. I don’t remember much about the article other than it motivated me to hunt the stacks, and maybe even climb a ladder, looking for it like:

‘Our Lady of the Nile’ is set in an eponymous Catholic high school for girls, the daughters of Rwanda’s elite class of military officials, businessmen and politicians. The school venerates and is named for a madonna painted black that is situated nearby at a source of the Nile River, which I had forgotten reached all the way south to Rwanda, like:

As you’ll see in the excerpt below, the teens attend the school to receive a Euro-centric education in anticipation of becoming wives of wealthy and powerful men, thus securing and improving the social and economic status of their families. The novel is constructed in an interesting way. Though it follows a group of girls over the course of a school year, you really can’t say that any one of them is the protagonist. Rather, the sum of all the moments and scenes we see from the students’ and teachers’ lives adds up to a narrative arc for the school, making it the main character. And that character metaphorically represents post-colonial Rwanda. It is a nifty bit of story crafting, and I always get a charge when authors are successful at finding unconventional ways to structure their stories, like:

The novel is set in what I believe is the 1960s, decades before the genocide that began in Rwanda 25 years ago this month. You can see the roots of that conflict — where the ethnic Hutu majority massacred the Tutsi minority — in how Hutu girls mock, torment and eventually demonize Tutsi girls who are allowed into the school through a quota system. (For additional reading about the genocide in Rwanda, I recommend ‘We Wish To Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families’ by Philip Gourevitch, and ‘A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide’ by Samantha Power.) In the final and most intense chapter of the book, a pair of Hutu girls decide the madonna by the river has a ‘Tutsi nose,’ which is intolerable. They decide to chip it off and replace it with a more suitable Hutu-shaped nose made from clay. But they end up shattering the statue’s head in the effort, and decide to blame fictitious Tutsi saboteurs for the act, which touches off a wave of deadly violence in the area. When one of the students has second thoughts, saying the troubles were brought about by lies, the other student waives her off, saying the most powerful and resonant line in the book: ‘It’s not lies, it’s politics.’ That line, which connects the book to our current political climate, had me like:

The book is full of memorable scenes and powerful metaphors. One highlight is when Rwanda’s president tries to give the childless king and queen of Belgium one of his young children in keeping with a local custom meant to ensure the Belgians would love and respect Rwanda and help it out of poverty. One of the school’s students would have served as the child’s translator. But the Belgians refuse. The president is left to marvel at the rudeness of Europeans, but the reader is left thinking about the legacy of colonialism and the inability of different cultures to understand each other. In another scene, an old Frenchman who lives on a coffee plantation near the school tells two Tutsi students that he believes Tutsis are descended from the lost tribe of Israel or the ancient Egyptians. He convinces one of them to dress up like the goddess Isis so he can paint her likeness on the walls of a temple he’s constructed on top of an ancient tomb. The student and her friend, whom the old man believes is the reincarnation of a queen named Candace, talk about how whites tend to dismiss, ignore and erase African culture and instead co-opt elements of that history and project onto it their own ideas and legends, like:

Not to give too much away, but the girl who participates in the old man’s project comes to a bad end, while the girl who is respectful of the spirit in the tomb does not. We readers are left to think about what we really know about the history and cultures of Africa, and what we can do to elevate and understand them in their own right, instead of filtering them through the prism of Europe. ‘Our Lady of the Nile’ is a good place to start, and I recommend this book wholeheartedly to you all.

How it begins:

There is no better lycée than Our Lady of the Nile. Nor is there any higher. Twenty-five hundred meters, the white teachers proudly proclaim. “Two thousand four hundred ninety-three meters,” points out Sister Lydwine, our geography teacher. “We’re so close to heaven,” whispers Mother Superior, clasping her hands together.

The school year coincides with the rainy season, so the lycée is often wrapped in clouds. Sometimes, not often, the sun peaks through and you can see as far as the big lake, that shiny blue puddle down in the valley.

It’s a girls’ lycée. The boys stay down in the capital. The reason for building the lycée so high up was to protect the girls, by keeping them far away from the temptations and evils of the big city. Good marriages await these young lycée ladies, you see. And they must be virgins when they wed — or at least not get pregnant beforehand. Staying a virgin is better, for marriage is a serious business. The lycée’s boarders are daughters of ministers, high-ranking army officers, businessmen, and rich merchants. Their daughters’ weddings are the stuff of politics, and the girls are proud of this — they know what they’re worth. Gone are the days when beauty was all that mattered. Their families will receive far more than cattle or the traditional jugs of beer for their dowry, they’ll get suitcases stuffed full of banknotes, or a healthy account with the Banque Belgolaise in Nairobi or Brussels. Thanks to their daughters, these families will grow wealthy, the power of their clans will be strengthened, and the influence of their lineage will spread far and wide. The young ladies of Our Lady of the Nile know just how much they are worth.

My rating:

‘Our Lady of the Nile’ (‘Notre-Dame du Nil’) by Scholastique Mukasonga was published by Éditions Gallimard in 2012, and by Archipelago Books in 2014. Translated from the French by Melanie Mauthner. 244 pages. $9 at Strand Book Store.

In two weeks you’ll get a review of ‘The Deeper the Water the Uglier the Fish’ by Katya Apekina. Also in the queue are ‘The Friend’ by Sigrid Nunez, ‘The Seas’ by Samantha Hunt and ‘The Autobiography of Gucci Mane’ by Gucci Mane, among others.

In case you missed it: Books on GIF #103 featured ‘Postcards From the Edge’ by Carrie Fisher.

Shoot me an email if there’s a bestseller, a classic or a forgotten gem you want reviewed.

Follow me on Twitter and Instagram.

Thanks for reading, and thanks especially to Donna for editing this review!

Until next time,

MPV