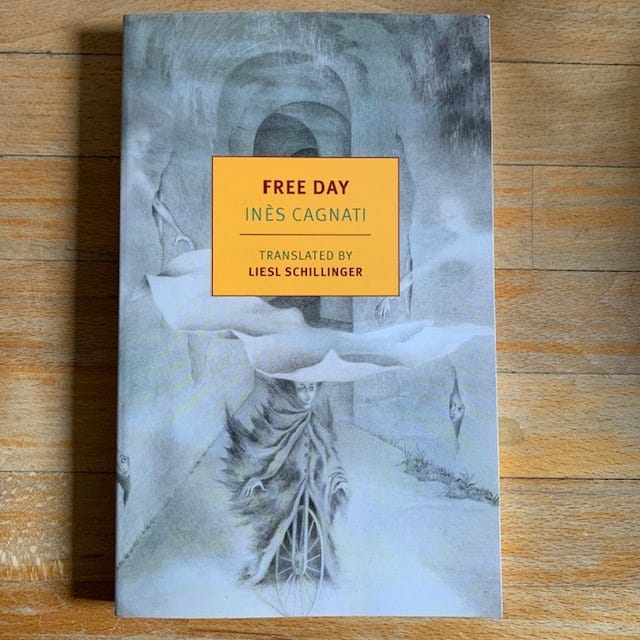

'Free Day' by Inès Cagnati + 'The Last Mosaic' by Elizabeth Cooperman & Thomas Walton

Review #133

As a throwback to last year’s ‘Novella November,’ here are reviews of two short books. One is an intense novel set in the French countryside. The other is a book of poetry that made me feel like I was back in Rome, which is one of my favorite places. This Sunday’s selections are ‘Free Day’ by Inès Cagnati and ‘The Last Mosaic’ by Elizabeth Cooperman and Thomas Walton. First up is ‘Free Day’:

Were you forwarded this email? Subscribe here.

This short novel opens with Galla having just arrived at her family farm in rural France after biking 20 miles from the town where she attends high school. Rather than head straight into the house where her parents and several younger sisters are, she remains outside and recalls moments from her childhood. While she’s wandering around the grounds and the surrounding area before choosing to settle in for the night with the dog in the barn, we hear about her tough life on the farm where the only bountiful crops seem to be domestic abuse, animal cruelty, human tragedy, and the stones she and her father constantly pull from the earth. We also see her struggles to fit in at the boarding school among her more well-off classmates and professors who don’t understand her. Galla says the reason she has returned to the farm—suddenly and unannounced—on her free day from school is to return a bag that she borrowed from her mother. But it becomes clear that she’s avoiding entering the house on purpose because:

Early in the story, her father comes out of the house and sees her. He yells at her to go away. Even after knowing how the story ends, which I won’t reveal here, I’m still puzzled over why he did that. Was it another form of his abuse? Or was it an act of love to protect her from what was happening inside? I think it has to do with Cagnati’s exploration of the family unit (which she explains in a bonus interview transcript at the end of the book) as something we simultaneously rebel from that also grounds us in the world. Galla has rebelled and done all she can to avoid confronting her family, yet she constantly thinks of them and yearns to be among them. It’s a fascinating and tense dynamic, and makes for an excellent story. You should read this book.

How it begins:

I leaned my bicycle against the wall of the barn and left it there. I could have kept on dragging it until it was in front of the house, as usual. It’s not more than fifty yards. But I’d had enough of my bicycle. Of pedaling. Of pushing it. Of pedaling. Of pushing it. And, in the end, carrying it. Completely enough. I’d had it. Because all of that had been going on for three or four hours, maybe more, even, and there comes a point when things have gone on long enough and you say: No.

On top of that, and as if by accident, a rain to end the world had been falling all those hours I was struggling with my bike. When I got home, it wasn’t raining anymore. Things like that happen, I’ve often noticed, always bad timing. As for the rain, so much water had fallen on the earth in those few hours that the clouds must have completely dried up. No surprise, then, that the filthy rain had stopped.

Anyway, none of that mattered to me. When I’m at home, I like to listen to the rain coming down hard. Ever since I’ve been going to the high school, I like being at home, whether it’s raining or nice out.

Of course, if I had my way. I would only like sunshine. The brightest sun. The most merciless. The kind whose weakest ray, touching the ground, opens broad cracks that cut deep into the heart of the earth. Under a sun like that, entire rivers dry up and disappear forever, drunk up by the sun. People, plants, animals, everything dies of thirst and of joy in the sun. Everything shines, rejoices, and dies. I’d like to live in a sunlit land like that. But I can’t dream about that. We’re not in a sunlit land here. Here it’s a land of marshes, mists, and fogs. There’s nothing I could do to change that, no matter how hard I dreamed. Even if I dreamed very, very hard. And I can’t dream. At our place, we need rain and sunshine. My father always says so. It’s for the crops, I understand. And also, if it didn’t rain, the well would run dry. The marshes, too. So there would be nothing to drink. We would die, along with everyone else. It would be fine with me if everyone else died—but not us.

My rating:

‘Free Day’ (‘Le Jour de Congé) was originally published by Éditions Denoël in 1973. Translated from the French by Liesl Schillinger and published by The New York Review of Books in 2019. 133 pages. I received it as part of a subscription.

Next up is ‘The Last Mosaic’:

Earlier, I described ‘The Last Mosaic’ as a book of poetry, but that only captures part of what’s offered in this smart and tiny book. Some of the bursts that fill the pages are poetic verses inspired by the Eternal City. Others offer facts and artistic statements about the locations and artwork found there. It’s the odd and interesting offspring of a Lonely Planet guide to Rome and a chapbook, where all the elements combine to form a literary mosaic of facts, history, art criticism and poetry. Reading Cooperman’s and Walton’s work evoked strong memories of walking through the streets, churches, museums and historical ruins of Rome, which might be slightly ahead of Paris as my second favorite city in the world. It made me yearn for a time when I could be like Audrey Hepburn in ‘Roman Holiday,’ and just spend a day in that city like:

I read this book back in February before the coronavirus kept us indoors. Thinking back on it now, it’s a bittersweet reminder of life before the pandemic, when we were free to roam around cities and examine art and architecture in situ, rather than through a computer screen. I hope those days can return soon. Until then, you should read this book.

Passages that stuck with me:

From page 87:

When you compare Giotto to his teacher Cimabue you can believe in the progress of art. I find this transformation—towards naturalism and away from pure didacticism—proof that humans will always be able to see themselves out of dark ages.

And a few verses later on page 88:

When you compare Hellenistic sculpture to the art of the Christian era you can believe in the degeneration of art. I find this transformation—toward pure didacticism, away from naturalism and aesthetic grace—proof that humans will always be able to see themselves into dark ages.

My rating:

‘The Last Mosaic’ by Elizabeth Cooperman and Thomas Walton was published by Sagging Meniscus Press in 2018. 121 pages. It was sent to me by the publisher.

More things worth your time:

Read these: Here are two pieces that explore how New York’s political leadership responded to the coronavirus outbreak. One was published this morning in The New Yorker: ‘Seattle’s Leaders Let Scientists Take the Lead. New York’s Did Not.’ It’s pretty scathing, especially for Mayor Bill de Blasio. The piece offers an inside look at how City Hall and Albany were slow to respond to the crisis, and let dithering, political calculations and public squabbling muddle and delay New York’s response to the crisis, which has killed tens of thousands here. Meanwhile, Seattle, which locked things down earlier, has seen far fewer deaths. Also, there’s this piece in Slate: ‘Nothing About New York’s Outbreak Was Inevitable.’ This article picks apart ‘New York exceptionalism’ and how it’s been used to hamper containing the virus. First, politicians argued that New York was so tough and exceptional that the virus wouldn’t be too bad here. Then, they argued that because the city is so dense that we are disproportionately more vulnerable than anywhere else. Both arguments are wrong, the piece argues.

Next week you will get a review of ‘A Fine Balance’ by Rohinton Mistry. Also in the queue are ‘The Bell Jar’ by Sylvia Plath, ‘The Decameron’ by Giovanni Boccaccio, and ‘S.P.Q.R.’ by Mary Beard, among others.

In case you missed it: Books on GIF #132 featured ‘Celestial Bodies’ by Jokha Alharthi.

Shoot me an email if there’s a bestseller, a classic or a forgotten gem you want reviewed.

Please click the heart button above if you enjoyed this newsletter. You can also share it with a friend:

Follow me on Twitter and Instagram.

Thanks for reading, and thanks especially to Donna for editing this newsletter!

Until next time,

MPV