'The Books of Jacob' by Olga Tokarczuk

'And how exactly would a saved world differ from an unsaved world?'—Review #209

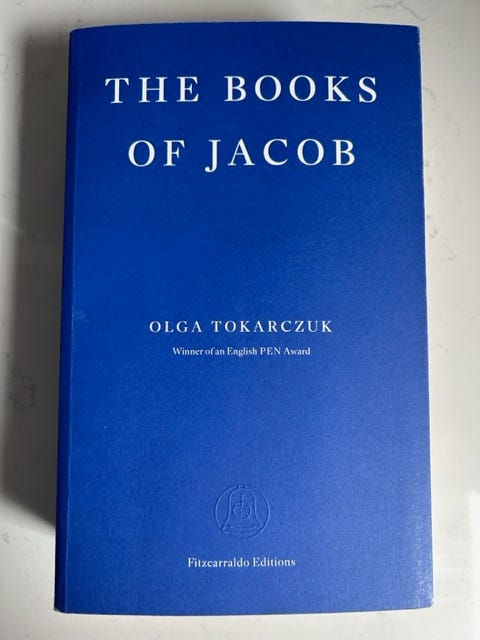

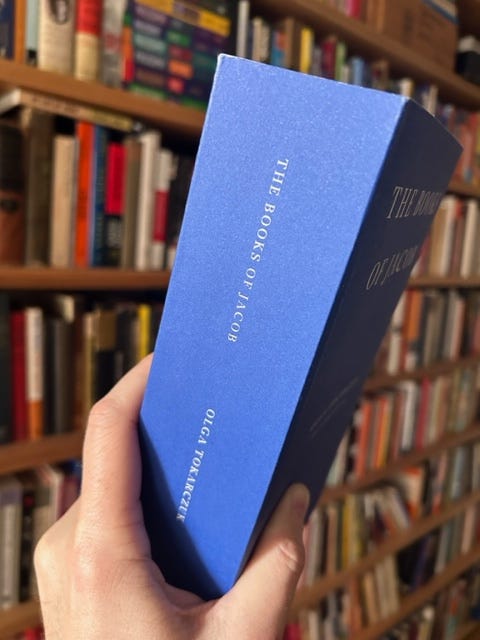

When I ordered Olga Tokarczuk’s novel ‘The Books of Jacob’ in early 2022, shortly after its English translation became available, I thought I’d read it right away. I previously reviewed two other novels of hers, ‘Flights’ and ‘Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead,’ and was eager to dive in. But then I saw how thick the book is. Look at this:

I was was like:

So I put it aside until our 7th anniversary newsletter came up when I would have two extra weeks to read the book, which was shortlisted for the 2022 International Booker Prize. Plenty of time, I thought. But it took me the entire month to get through it, reading it at night before bed, on the subway during my commute and in the waiting room before a doctor’s visit, as well as sneaking snippets while Donna was distracted by Spelling Bee. My thumb hurts from holding the book. I barely finished it in time for this review.

Here’s the cover:

‘The Books of Jacob’ follows Jacob Frank, a real-life figure who formed a breakaway religious sect that attracted a cult-like following among some Jews in eastern Europe, particularly in what’s now Poland and Ukraine, in the mid to late 1700s. Some of the sect’s beliefs, as described in the novel, included that salvation would come by embracing elements of Christianity, like the Trinity and being baptized by the Catholic Church, and weird sexual rituals. Frank himself was like:

Jewish leaders condemned Frank and his followers as heretics. But Catholic leaders were intrigued by them as a potential means to converting Jews to Christianity. Throughout the novel, Frank and his entourage are constantly in flight, evading pogroms, persecution and plagues, while trying to convince local kings and nobles to give them some land where they could live and practice their religion. We see them go from the European frontier of the Ottoman Empire, through Poland to Austria and, eventually, to Germany. Their journey is observed by an all-seeing elderly woman named Yente, who dwells between the realms of the living and the dead due to a magical amulet. The novel is divided into a series of sections, or ‘books,’ that are composed of a dense and detailed narrative, as well as letters and some hard-to-see renderings of historical documents and images. The page numbers count down from 892, in an effort to evoke Hebrew texts that are read from right to left, like:

I struggled to connect to Frank’s story, but I’ll be thinking about what it might mean for a while. Is it about how people grappling with a world that is bleak, unforgiving and scary turn over their lives to charismatic figures for safety and structure? Or about how in the duration of one person’s lifetime the world can see dramatic and historic change? The book begins in a literal fog among impoverished serfs and ends in the Age of Enlightenment. Or maybe it’s just a novelization of the life of an interesting figure from history. (If you’ve read this book, let me know your thoughts in the comments.) Either way, I’m glad I finally read this massive tome. I’ll read something shorter next.

How it begins:

Once swallowed, the piece of paper lodges in her oesophagus near her heart. Saliva-soaked. The specially prepared black ink dissolves slowly now, the letters losing their shapes. Within the human body, the word splits in two: substance and essence. When the former goes, the latter, formlessly abiding, may be absorbed into the body’s tissues, since essences always seek carriers in matter—even if this is to be the cause of many misfortunes.

Yente wakes up. But she was just almost dead! She feels this distinctly now, like a pain, like the river’s current—a tremor, a clamour, a rush.

With a delicate vibration, her heart resumes its weak but regular beating, capable. Warmth is restored to her bony, withered chest. Yente blinks and just barely lifts her eyelids again. She sees the agonized face of Elisha Shorr, who leans in over her. She tries to smile, but that much power over her face she can’t quite summon. Elisha Shorr’s brow is furrowed, his gaze brimming with resentment. His lips move, but no sound reaches Yente. Old Shorr’s big hands appear from somewhere, reaching for her neck, then move beneath her threadbare blanket. Clumsily he rolls her body onto the side, so he can check the bedding. Yente can’t feel his exertions, no—she senses only warmth, and the presence of a sweaty, bearded man.

Then suddenly, as though from some unexpected impact, Yente sees everything from above: herself, the balding top of old Shorr’s head—in his struggle with her body, he has lost his cap.

And this is how it is now, how it will be: Yente sees all.

Who they thanked:

Tokarczuk includes a section on sources, and also separate acknowledgements where she thanks those who helped with research for the book as well as ‘those I have been tormenting for years now with stories of the Frankists.’ Translator Jennifer Croft thanks various institutions for financial support, and also her agent and her husband. In addition, Croft thanks ‘the community of Olga’s translators into many world languages for regularly exchanging questions and ideas.’

My rating:

‘The Books of Jacob’ by Olga Tokarczuk was published by Wydawnictwo Literackie in 2014 and by Fitzcarraldo Editions in 2021. Translated from the Polish by Jennifer Croft. 892 pages. $18.60 at Bookshop.org.

What’s next:

Before you go:

ICYMI:

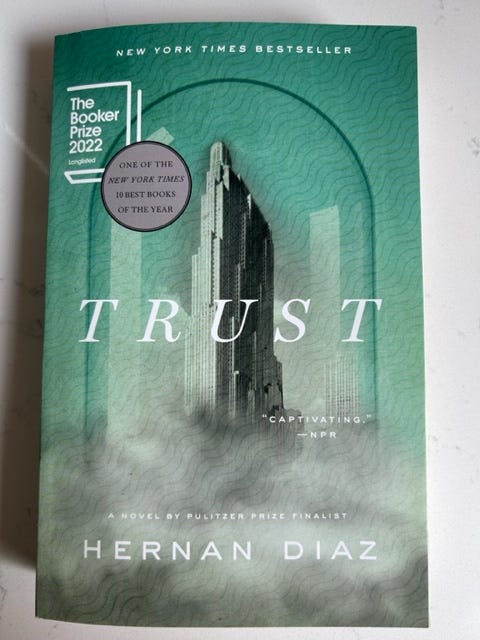

Read this: This week’s New York Times Book Review includes an interesting interview with Hernan Diaz: ‘Some of the Books That Hernan Diaz Owns Surprise Even Him.’ I’m excited to start reading his Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, ‘Trust,’ this week.

If you enjoyed this review:

Thanks for reading, and thanks especially to Donna for editing this newsletter!

MPV

I like the last gif 'it is a lot'... I was on Notes and saw a 'subscribe' link next to your name. Don't know if it was a glitch or that we have to subscribe to people for Notes. I've definitely not unsubscribed from the email list, but I clicked again anyway. Substack's little glitchy with new updates. And Notes seems really alive at the moment. Unlike twitter where reach is almost dead. good to see a new gif-fy review

I feel you. I dislike lengthy books too 😂